Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Bheki Mseleku was born Bhekumuzi Hyacinth Mseleku on March 3, 1955 in South Africa. Entirely self-taught, though his father was a musician and teacher, his religious belief denied musical access to his children. Growing up in Apartheid he was subjected to restricted healthcare and lost the upper joints of two fingers in a go-karting accident.

His musical career began in Johannesburg in 1975 as an electric organ player for the R&B band Spirits Rejoice. After performing at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1977, Mseleku settled in Botswana for a time, then moved to London in the late 1970s. He attempted to settle into the jazz scene in Stockholm from 1980 to 1983, but returned to London. It was not until 1987 that Bheki made his debut at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, playing piano unaccompanied by other musicians, with a saxophone in his lap that a wider audience became familiar.

With the release and notoriety of his 1991 debut album Celebration, and subsequent nomination for a Mercury Music Prize that Verve Records signed him for several albums. The first of these featured Joe Henderson, Abbey Lincoln, and Elvin Jones.

Twelve years and five albums later Bheki recorded his final session “Home at Last” in 2003, having spent most of his last years in South Africa. He never found an outlet for his skills and established a new band in London that was very well received by fans. Over the course of his life Bheki Mseleku lived with diabetes and on September 9, 2008 the pianist, saxophonist, guitarist, composer and arranger passed away in his London flat at age 53.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Orrin Keepnews born March 2, 1923 in Bronx borough of New York City and graduated from Columbia University with a degree in English in 1943. And was subsequently involved in bombing raids over Japan in the final months of World War II before returning for graduate studies at Columbia in 1946.

While working as an editor for the book publishers Simon & Schuster he moonlighted as editor of The Record Changer magazine in 1948 and by 1952 along with the magazine’s owner Bill Grauer, produced a series of reissues on RCA Victor’s Label “X”. The following year they founded Riverside Records, which was originally devoted to reissue projects in the traditional and swing jazz idioms.

Signing pianist Randy Weston was the label’s first modern jazz artist, who helped them to begin paying attention to the current jazz scene. Their most significant early move came in 1955, when they were made aware of the availability of Thelonious Monk, who was leaving Prestige and from this point, the label concentrated on the burgeoning modern jazz scene.

Keepnews produced significant young artists as Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley, Wes Montgomery, Johnny Griffin, Jimmy Heath and was soon rivaling Blue Note and Prestige as a New York independent jazz label. In 1961, Keepnews produced what many regard as one of the greatest live jazz recordings of all time with the Bill Evans Trio, Sunday At The Village Vanguard and Waltz For Debby. However, in 1963 Grauer died of a heart attack and a year later the company was bankrupt, closing the Riverside doors. Not to be trumped, Keepnews founded Milestone Records in ’66 and released albums by McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Lee Konitz and Gary Bartz. 1972 saw him in San Francisco as jazz A&R for Fantasy Records who bought both Riverside and Milestone masters.

Returning to freelancing he opened the doors of Landmark Records in 1985 that eventually passed to Muse Records in 1993. Over the course of his career he has won several Grammy Awards, including Best Album Notes and Best Historical Album; was given the Trustees Award for Lifetime Achievement, received an NEA Jazz Masters Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 in the field of jazz.

He continued to be responsible for extensive reissue compilations, including the Duke Ellington 24CD RCA Centennial set in 1999 and Riverside’s Keepnews Editions series. Orrin Keepnews, writer and record producer, passed away on March 1, 2015 in El Cerrito, California.

More Posts: record producer,writer

Requisites

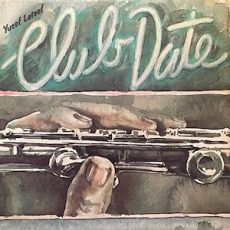

Club Date ~ Yusef Lateef | By Eddie Carter

A few nights ago, I spent time with an album I hadn’t listened to in a while and thought it deserved discussing. Club Date (ABC Impulse ASD-9310), by multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef, was released in 1976 and showcases his live performance at Pep’s Lounge on June 29, 1964, first heard on Live at Pep’s. My introduction to Lateef’s artistry came through his work on Cannonball Adderley Sextet in New York, Nippon Soul, and Jazz Workshop Revisited. The tracks on Club Date were not available before this release. The group includes Richard Williams on trumpet; Yusef Lateef on flute (tracks B1, B3), oboe (track B1), and tenor saxophone (tracks A1 to A3, B2); Mike Nock on piano; Ernie Farrow on bass; and James Black on drums. The copy I own is the 1976 U.S. Stereo release.

The set opens with Oscarlypso by Oscar Pettiford, a lively tune featuring a Caribbean groove from the start of Ernie’s introduction to the quintet’s theme. Yusef takes the opening solo, as smooth as velvet. Richard follows with a cheerfully festive performance. Mike enters the spotlight last, with a relaxing reading, before both horns share a short exchange leading to the reprise and a vibrant finish. Gee Sam Gee by Yusef Lateef is a slow-moving ballad that begins with the saxophonist stating a hauntingly dreamy theme and opening solo. Williams and Nock follow with two delicately gentle statements preceding Lateef’s return for the closing chorus.

Richard Williams’ Rogi brings the beat way up to end the first side with the group’s collective melody. Yusef steps up first with a spirited performance, then Richard vigorously launches into the following solo. Mike has the last word with an energetic statement ahead of the theme’s return and climax. Brother John, Yusef Lateef’s tribute to John Coltrane, opens the second side with the rhythm section’s trio to Lateef’s switching to oboe for the melody and adventurous opening statement. Williams takes flight next in a scintillating solo. Nock keeps the listener captivated, sailing smoothly until the final note, while Yusef’s flute comments shadow him, before the quintet returns to take the song out.

Yusef Lateef introduces P-Bouk, a speedy original by the saxophonist that the ensemble takes out of the gate at a vigorous pace. Yusef soars upward into the sky on the opening solo with joyful exhilaration. Richard comes in cooking hard next, then Mike meets the challenge with a robust reading, leading to the theme’s restatement and the introduction of Nu-Bouk, also by Yusef Lateef, which he describes as a new blues. He’s back on the flute as he glides over the rhythm section for the soulful melody and lead solo. Williams makes his case in a short statement, returning to the theme and the group’s down-home ending.

Bob Thiele produced the initial session for Club Date, and Esmond Edwards supervised this release, but the identity of the engineer who recorded it remains unknown. The sound quality is very good for a ‘60s live date, with an excellent soundstage that transports the listener to the club’s audience. If you’re new to the music of Yusef Lateef, or are in the mood for a wonderful live album to listen to after a long day or week, I offer for your consideration Club Date by Yusef Lateef. It gives a glimpse into an incredible musician who transcended hard bop through music inspired by exotic locales. While the recording’s live atmosphere adds raw authenticity, it’s the interplay among the players that truly shines, making this record a rewarding listen for both longtime fans and newcomers to Lateef’s work!

~ Cannonball Adderley Sextet in New York (Riverside RLP-404/RLP-9404), Jazz Workshop Revisited (Riverside RM 444/RS 9444), Live at Pep’s (Impulse! A-69/AS-69), Nippon Soul (Riverside RM 477/RS 9477) – Source: JazzStandards.com

© 2026 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Norman Connors was born on March 1, 1947 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He became interested in jazz as a child when he began to play drums and while in middle school once sat in for Elvin Jones at a John Coltrane performance. He continuing music studies took him to Temple University and Julliard.

His first recording was on Archie Shepp’s 1967 release, Magic of JuJu and then played with Pharoah Sanders for the next few years. In 1972 he signed with Cobblestone Records and released his first album as a leader. He went on to front some great jazz recordings with Carlos Garnett, Gary Bartz, Dee Dee Bridgewater and Herbie Hancock such as “Love From the Sun”.

By the mid 70s Norman’s focus leaned more towards R&B, scoring several U.S. hits with songs and love ballads featuring guest vocalists such as Michael Henderson, Jean Carn and Phyllis Hyman. He also produced recordings for various artists, including collaborations with Carn and Hyman and also Norman Brown, Al Johnson, and Marion Meadows.

Norman Connors is a drummer, composer, arranger and producer who has recorded for Buddah, Arista, Capitol, Motown and Shanachie record labels; worked with Howard Hewitt, Bobby Lyle, Ray Parker Jr., Peabo Bryson and Antoinette and has since ventured into disco and smooth jazz and urban crossover arenas.

More Posts: drums

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

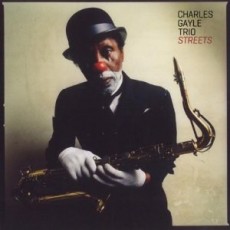

Charles Gayle was born February 28, 1939 in Buffalo, New York and his childhood was influenced by religion, and his musical roots trace to black gospel music. He began his musical education on piano then added tenor and alto saxophone. Much of his history is murky, he spent an apparent homeless period of about twenty years playing saxophone on street corners and subway platforms around New York City.

A multi-instrumentalist playing pianist, bass clarinetist and percussion, his music is spiritual, heavily inspired by the Old and New Testaments, explicitly dedicated several albums to God. Gayle credits among his influences Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Thelonious Monk and Art Tatum.In 1988, he gained fame through a trio of albums recorded on the Swedish label Silkheart Records. Since then he has become a major figure in free jazz, recording for Black Saint, Knitting Factory, FMP and Clean Feed record labels.

Charles has performed and recorded with Cecil Taylor, William Parker and Rashied Ali with his most celebrated work to date being Touchin’ on Trane with Parker and Ali. He would include lengthy spoken-word addresses in his performances and for a period performed as a mime, “Streets the Clown”. As an educator he taught music at Bennington College.

In 2001, Gayle recorded an album titled Jazz Solo Piano of consisted mostly of straightforward jazz standards in response to critics who charge that free jazz musicians cannot play bebop. In 2006, Gayle followed up with a second album of solo piano originals, and his most recent release in 2012 is titled Streets. His final recording as a leader was The Alto Sessions in 2019.

Suffering from complications of Alzheimer’s disease, saxophonist Charles Gayle, who also played piani, bass clarinet, bass and percussion, died in Brooklyn, New York on September 7, 2023 at the age of 84.