Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Eddie Higgins was born Edward Haydn Higgins on February 21, 1932 in Cambridge, Massachusetts and began study of piano with his mother. His professional career began in Chicago while attending Northwestern University. He played the most prestigious clubs in Chicago for more than two decades in the 50s and 60s with his longest tenure at the London House, playing opposite Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Errol Garner, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson, and George Shearing among others.

As a leader he amassed a number of recordings during the Chicago years but as a sideman he added many more albums working with Wayne Shorter, Coleman Hawkins, Bobby Lewis, Freddie Hubbard, Jack Teagarden and Al Grey to name just a few.

Equally adept in every jazz circle Eddie was able to work in Dixieland, modal, bebop and swing as well as being a persuasive, elegant and sophisticated pianist whether he was soloing or accompanying a singer.

Higgins eventually moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, played in local clubs, performed the jazz festival circuit, toured Europe and Japan, and continued to record up until his death on August 31, 2009 at 77.

More Posts: piano

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Nancy Wilson was born February 20, 1937 in Chillicothe, Ohio and at an early age was listening to Billy Eckstine, Nat Cole, Dinah Washington, Ruth Brown, LaVerne Baker, Little Esther and Jimmy Scott. She became aware of her talent while singing in church choirs, imitating singers as a young child and performing in her grandmother’s house during summer visits. By the age of four, she knew she would eventually become a singer.

At the age of 15, while at West High School in Columbus she won a talent contest sponsored by local television station WTVN. The prize was an appearance on a twice-a-week television show, Skyline Melodies, which she ended up hosting. She also worked clubs on the east and north sides of Columbus until she graduated from high school.

She spent one year at Ohio Central State College to become a teacher but dropped out to follow her original ambitions. She auditioned and won a spot with Rusty Bryant’s Carolyn Club Big Band in 1956, touring with them throughout Canada and the Midwest in 1956 to 1958. While in this group, Nancy made her first recording for Dots Records.

Nancy met Cannonball Adderley who suggested she move to New York that she did in 1959. Within four weeks she was filling in for Irene Reid at “The Blue Morocco” that booked her permanently four nights a week. With John Levy as her manager, who sent four demos to Capitol Records culminating with a contract signed in 1960 and recorded her debut release “Like In Love”.

Over the course of her career Nancy won three Grammy Awards, was nominated seven times, recorded more than six dozen albums, appeared in four movies, and sixteen television shows ranging from drama to comedy.

Song stylist and vocalist Nancy Wilson passed away on December 13, 2018, at her home in Pioneertown, California at 81 years old.

More Posts: vocal

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Jean-Paul Maunick was born February 19, 1957 in Mauritius to poet Edouard Maunick. At the age of nine his family moved to the United Kingdom and learning to play the guitar began his journey in music.

A founding member of the group Light of the World, Maunick formed the British acid jazz band Incognito in 1979 and released his debut album “Jazz Funk” in 1981. Bluey, as he is known to most, has fused funk, R&B, Brazilians rhythms and soul into a sound that has captured and kept the world’s attention. In addition to releasing fourteen studio albums as well as several live albums, remix albums and compilation albums.

His group dynamic has changed over the years as he has brought singers Jocelyn Brown, Carleen Anderson, Tony Momrelle, Imaani, Maysa Leak Kelli Sae of Count Basic and Joy Malcom to take the lead vocal position. His record production credits include artists such as Paul Weller, George Benson, Maxi Priest, and Terry Callier, having also collaborated with Stevie Wonder.

Guitarist, bandleader, composer and record producer Jean Paul Maunick, better known as Bluey, continues to explore new directions in music performing and touring worldwide.

More Posts: guitar

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

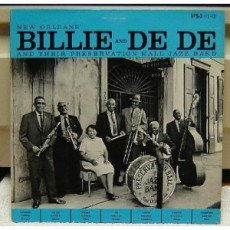

De De Pierce was born Joseph De Lacroix Pierce on February 18, 1904 in New Orleans, Louisiana. A trumpeter and cornetist, his first gig was with Arnold Dupas in 1924. During his time playing in New Orleans nightclubs he met Billie Pierce, who became his wife as well as a musical companion. They took residence as the house band at the Luthjens Dance Hall from the 1930s through the 1950s.

They released several albums together but stopped performing in the middle of the 1950s due to illness, which left De De Pierce blind. By 1959 they had returned to performing with De De touring with Ida Cox and playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band before further health problems ended his career.

On November 23, 1973, De De Pierce, best remembered for the songs “Peanut Vendor” and “Dippermouth Blues”, passed away at the age of 69.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

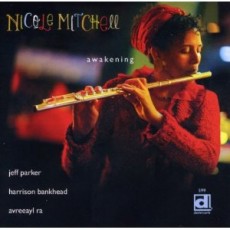

Nicole Mitchell was born on February 17, 1967 in Syracuse, New York where she was raised until age eight, when her family moved to Anaheim, California. She began with piano and viola in the fourth grade; however, she was classically trained in flute and played in youth orchestras as a teenager. Her initial college major in math was superseded by jazz while in college and took to busking in the streets playing jazz flute. After two years at the University of California, San Diego, in 1987 she transferred to Oberlin College.

In 1990 a move to Chicago saw her playing once again on the streets and working for third World Press and meeting members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Mitchell soon started playing with the all-women ensemble Samana under the AACM umbrella. Over the next several years she moved to New Orleans, became a mother, returned to school earning her BA and Masters, met and extensively began playing with Hamid Drake, then worked with saxophonist David Boykin prior to starting her group the Black Earth Ensemble” and co-hosting the Avant-Garde Jazz Jam Sessions in Chicago.

Releasing her debut album “Vision Quest” in 2001, she has been named “Rising Star” flautist for 2004 -2006 by Down Beat and by Down Beat International Critics Poll in 2010 & 2011. As an educator, Nicole has taught at Northern Illinois, Chicago State, Northeastern Illinois University, Wheaton College and the University of Illinois at Chicago; and has been co-president of the AACM since 2006.

More Posts: flute