Daily Dose Of Jazz…

De De Pierce was born Joseph De Lacroix Pierce on February 18, 1904 in New Orleans, Louisiana. A trumpeter and cornetist, his first gig was with Arnold Dupas in 1924. During his time playing in New Orleans nightclubs he met Billie Pierce, who became his wife as well as a musical companion. They took residence as the house band at the Luthjens Dance Hall from the 1930s through the 1950s.

They released several albums together but stopped performing in the middle of the 1950s due to illness, which left De De Pierce blind. By 1959 they had returned to performing with De De touring with Ida Cox and playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band before further health problems ended his career.

On November 23, 1973, De De Pierce, best remembered for the songs “Peanut Vendor” and “Dippermouth Blues”, passed away at the age of 69.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Walter “Rosetta” Fuller was born on February 15, 1910 in Dyersburg, Tennessee, first learning to play the mellophone as a child before settling on trumpet. He played in a traveling medicine show from age 14, then played with Sammy Stewart in the late 1920s.

Fuller In 1930 he moved to Chicago and played with Irene Eadie and Her Vogue Vagabonds. In 1931 he began a longtime partnership with Earl Hines, remaining with him until 1937, when he left to join Horace Henderson’s ensemble. After a year with Henderson he returned to Hines’ band but once again left Hines in 1940 to form his own band, playing at the Grand Terrace in Chicago and the Radio Room in Los Angeles. Among his sidemen were Rozelle Claxton, Quinn Wilson, Omer Simeon and Gene Ammons.

Fuller got the nickname “Rosetta” based on his singing on the 1934 Hines recording of the song of the same name. He would lead bands on the West Coast for over a decade and play as a sideman for many years afterward. On April 20, 2003 trumpeter and vocalist Walter Fuller passed away in San Diego, California.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Emanuel Sayles: The Banjoist Who Followed the Music HomeEmanuel Sayles was born on January 31, 1907, in Pensacola, Florida, and began his musical education in the classical tradition, playing violin and viola as a child. But the jazz spirit was calling, and Sayles answered by teaching himself banjo and guitar, the instruments that would define his career and connect him to the early New Orleans jazz tradition.

Following the Music to New Orleans

After high school, Sayles made the pilgrimage that so many musicians made: he relocated to New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, where he joined William Ridgely’s Tuxedo Orchestra, a prestigious gig that put him in the center of the city’s vibrant music scene.

What followed was a classic New Orleans apprenticeship: Sayles worked with the legendary pianist Fate Marable, violinist Armand Piron, and trumpeter Sidney Desvigne on Mississippi riverboats, those floating conservatories where musicians learned to swing, read charts, and play for dancers night after night. The riverboat gigs were grueling but invaluable, connecting Sayles to the earliest generations of jazz musicians and teaching him the repertoire that would sustain him for decades.

Making History in Chicago

In 1929, Sayles participated in recordings with the Jones-Collins Astoria Hot Eight—sessions that captured the raw, collective improvisation style of early New Orleans jazz before it became codified and nostalgic. These recordings remain treasured documents of a transitional moment in jazz history.

By 1933, Sayles had moved to Chicago, where he led his own group and became a sought-after accompanist on blues and jazz recordings, working frequently with the great barrelhouse pianist Roosevelt Sykes and others. Chicago in the 1930s was electric with blues and swing, and Sayles’ banjo added that distinctive rhythmic drive that made everything move.

Always Returning to New Orleans

In 1949, Sayles returned to New Orleans, the first of several homecomings, and joined forces with clarinetist George Lewis, one of the leading voices in the New Orleans traditional jazz revival. In 1963-64, he toured Japan with Lewis, bringing authentic New Orleans jazz to audiences halfway around the world who were hungry to hear the music in its original form.

Back in New Orleans, he played with the beloved pianist Sweet Emma Barrett, then traveled to Cleveland in 1960 to work with trumpeter Punch Miller. From 1965 to 1967, he was back in Chicago playing in the house band at the Jazz Ltd. Club, one of the premier traditional jazz venues in the country.

Preservation Hall and the Final Chapter

Returning once more to New Orleans in 1968, Sayles found his spiritual home with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, the ensemble dedicated to keeping the traditional New Orleans sound alive for new generations. Preservation Hall wasn’t just a venue, it was a mission, and Sayles was perfectly suited to be part of it.

Documenting the Tradition

Sayles recorded prolifically as a sideman with cornetist Peter Bocage, trumpeter Kid Thomas Valentine, pianist Earl Hines, and drummer Louis Cottrell, each session a masterclass in the early New Orleans ensemble style. As a leader, he recorded extensively throughout the 1960s for GHB, Nobility, Dixie, and Big Lou record labels, ensuring that his particular approach to the banjo, rhythmically propulsive, harmonically sophisticated, never overplaying, would be preserved for future students of the tradition.

The Unsung Rhythm Master

Emanuel Sayles passed away on October 5, 1986, having spent nearly eight decades playing the music he loved. As a master banjoist, he represented something increasingly rare: a direct connection to the earliest days of jazz, when the banjo was king of the rhythm section and New Orleans was the only place the music existed.

Why His Story Matters

Sayles’ career is a reminder that jazz history isn’t just about the innovators who pushed the music forward, it’s also about the dedicated musicians who preserved what came before, who understood that the old New Orleans collective improvisation style had value and beauty that shouldn’t be lost in the rush toward bebop and beyond.

Every time he returned to New Orleans—and he kept returning, Sayles was affirming that the music’s roots mattered, that there was wisdom in the way the old-timers played, that the banjo had a place even as guitars became dominant. From Pensacola to riverboats to Chicago clubs to Preservation Hall, Emanuel Sayles followed the music wherever it led and always, eventually, back home to New Orleans, where it all began.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Tiny Winters: The Bassist Who Fooled Fans Into Thinking He Was Ella Fitzgerald

Frederick Gittens was born on January 24, 1909, in London, England, but the jazz world would come to know him by a name that became legendary in British jazz circles: Tiny Winters.

From Violin to the Bass That Swings

He learned violin as a child—a common enough beginning—but something about the double bass called to him. He made the switch and developed a pizzicato style directly inspired by the great New Orleans bassist Pops Foster, whose propulsive walking lines and rhythmic drive had helped define early jazz. Winters was absorbing American jazz from across the Atlantic and making it his own.

Rising Through Britain’s Jazz Scene

By the 1920s, he was already working with the Roy Fox Band, one of Britain’s premier dance orchestras. The 1930s brought collaboration with pianist and arranger Lew Stone, whose sophisticated arrangements were pushing British jazz toward new heights.

But here’s where Winters’ story gets delightfully unusual: he possessed an unusually high vocal range that he put to remarkable use covering Ella Fitzgerald hits. His falsetto was so convincing that he regularly received fan mail addressed to “Miss Tiny Winters.” Imagine the surprise of fans who showed up expecting a female vocalist and discovered a bassist with a four-octave range!

Becoming a Bandleader and Session Ace

Winters went on to play with the elegant Ray Noble, recorded with the great American tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins when he visited London, and began leading his own groups by 1936. With his reputation firmly established, he became a regular fixture at the fashionable Hatchett Club while freelancing as a sought-after session player in theatrical orchestras for major productions like Annie Get Your Gun and West Side Story.

Comedy, Television, and New Ventures

Later in his career, Winters played with cornetist Digby Fairweather in the Kettner’s Five, recorded with veteran saxophonist Benny Waters, and became both the bassist and featured comedian with trombonist George Chisholm in The Black and White Minstrel Show—a television variety program that showcased his versatility as an entertainer, not just a musician.

The Final Chapters

During the late 1980s, Winters led the Café Society Orchestra and his own Palm Court Trio, proving that age hadn’t diminished his passion for leading ensembles. He also found time to write his autobiography, cheekily titled It Took a Lot of Pluck—a perfect pun for a bassist whose fingers had plucked millions of notes over seven decades.

When he retired in the 1990s, he did so with honor: Winters was awarded the Freedom of the City of London, a historic recognition that acknowledged not just his musical contributions but his status as a beloved cultural figure.

A Life Well Lived

Bassist, vocalist, comedian, and bandleader Tiny Winters passed away on February 7, 1996, leaving behind a legacy that reminds us jazz wasn’t just an American export—it was reimagined, reinterpreted, and reinvigorated by musicians around the world who made it their own.

From fooling fans with his Ella Fitzgerald impersonations to holding down the bass in London’s finest orchestras for seventy years, Tiny Winters proved that sometimes the most interesting careers are the ones that refuse to fit into neat categories.

More Posts: bass

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

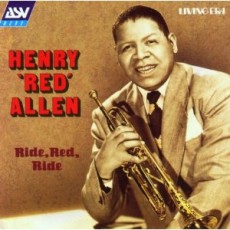

Henry “Red” Allen: The Trumpet Voice That Defined an Era

Born Henry James Allen on January 7, 1906, in the storied Algiers neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, Red Allen grew up surrounded by the very birthplace of jazz. With a trumpet in hand from early childhood, he seemed destined to become one of the instrument’s most distinctive voices.

A New Orleans Beginning

By his late teens, young Henry was already turning heads, performing with Sidney Desvigne’s Southern Syncopators. The education continued: by 1924, he was playing professionally with the legendary Excelsior Brass Band and various jazz dance bands that kept New Orleans swinging. Like so many musicians of his generation, Allen honed his craft aboard the Mississippi riverboats—floating conservatories where the music never stopped and every night brought new challenges.

The Journey North

In 1927, Allen’s talent took him to Chicago, where he joined the great King Oliver and began recording as a sideman with Clarence Williams. But the real prize lay further east. A move to New York City brought him a coveted recording contract with Victor Records—a major breakthrough for any young musician.

The year 1929 marked a pivotal moment: Allen joined Luis Russell’s Orchestra, where he became a featured soloist and remained until 1932. His fiery, inventive playing began appearing on recording sessions with Eddie Condon, and by late 1931, he was making a series of memorable recordings with Don Redman.

A Who’s Who of Jazz Collaborations

From 1933 to 1934, Allen brought his sound to Fletcher Henderson’s celebrated Orchestra. What followed was a dizzying roster of collaborations that reads like a jazz history textbook: he played with the orchestras of Lucky Millinder and Luis Russell, toured Europe with Kid Ory, and worked or recorded with Coleman Hawkins, Tommy Dorsey, Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, Victoria Spivey, and the incomparable Billie Holiday.

Leading from the Front

As a bandleader in his own right, Allen recorded for virtually every major label of the era—ARC, Decca, Okeh, Vocalion, Brunswick, and Apollo. He led his own ensemble at iconic New York venues like the Famous Door and the Metropole Café, toured extensively across the United States and Europe, and even graced television screens with an appearance on “The Sound of Jazz.”

A Courageous Final Chapter

When Allen was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in late 1966, he faced the news with characteristic determination. Even after surgery, he insisted on one final tour of England—a testament to his lifelong dedication to the music and the audiences who loved him. That tour concluded just six weeks before his death on April 17, 1967, in New York City.

Henry “Red” Allen left behind more than recordings and memories—he left a trumpet legacy marked by innovation, passion, and an unmistakable sound that still resonates through jazz history today.

More Posts: trumpet