Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Eddie Higgins was born Edward Haydn Higgins on February 21, 1932 in Cambridge, Massachusetts and began study of piano with his mother. His professional career began in Chicago while attending Northwestern University. He played the most prestigious clubs in Chicago for more than two decades in the 50s and 60s with his longest tenure at the London House, playing opposite Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Errol Garner, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson, and George Shearing among others.

As a leader he amassed a number of recordings during the Chicago years but as a sideman he added many more albums working with Wayne Shorter, Coleman Hawkins, Bobby Lewis, Freddie Hubbard, Jack Teagarden and Al Grey to name just a few.

Equally adept in every jazz circle Eddie was able to work in Dixieland, modal, bebop and swing as well as being a persuasive, elegant and sophisticated pianist whether he was soloing or accompanying a singer.

Higgins eventually moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, played in local clubs, performed the jazz festival circuit, toured Europe and Japan, and continued to record up until his death on August 31, 2009 at 77.

More Posts: piano

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

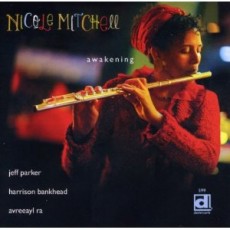

Nicole Mitchell was born on February 17, 1967 in Syracuse, New York where she was raised until age eight, when her family moved to Anaheim, California. She began with piano and viola in the fourth grade; however, she was classically trained in flute and played in youth orchestras as a teenager. Her initial college major in math was superseded by jazz while in college and took to busking in the streets playing jazz flute. After two years at the University of California, San Diego, in 1987 she transferred to Oberlin College.

In 1990 a move to Chicago saw her playing once again on the streets and working for third World Press and meeting members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Mitchell soon started playing with the all-women ensemble Samana under the AACM umbrella. Over the next several years she moved to New Orleans, became a mother, returned to school earning her BA and Masters, met and extensively began playing with Hamid Drake, then worked with saxophonist David Boykin prior to starting her group the Black Earth Ensemble” and co-hosting the Avant-Garde Jazz Jam Sessions in Chicago.

Releasing her debut album “Vision Quest” in 2001, she has been named “Rising Star” flautist for 2004 -2006 by Down Beat and by Down Beat International Critics Poll in 2010 & 2011. As an educator, Nicole has taught at Northern Illinois, Chicago State, Northeastern Illinois University, Wheaton College and the University of Illinois at Chicago; and has been co-president of the AACM since 2006.

More Posts: flute

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Maceo Parker was born February 14, 1943 in Kinston, North Carolina and was exposed to music early in life within his family and learned to play the saxophone. He and his brother Melvin, who played drums, joined James Brown in 1964 a relationship that lasted for six year before he left with Melvin and a few other Brown band members to form Maceo & All The King’s Men in 1970.

By ’74 he was back with Brown, charted a party single with Maceo & The Macks, joined Parliament-Funkadelic in the late 70s into the 89s, and then returned once again to James Brown for four years late in the decade. In the 1990s, Parker began his successful solo career releasing ten albums and performing 100 to 150 dates a year.

He has guest appeared on a variety of group’s albums and concerts and turning to jazz recorded “Roots & Grooves” with the WDR Big Band to critical acclaim as a tribute to Ray Charles. The album won a Jammie for best Jazz Album in 2009.

In October 2011 soul jazz saxophonist Maceo Parker was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame. He continues touring throughout the world, headlining the major Jazz Festivals in Europe where his following is at its strongest.

More Posts: saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Ron Jefferson was born on February 13, 1926 in New York City and began as a tap dancer before taking up the drums. He quickly became a fixture on the postwar bop scene collaborating, touring and/or recording with Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Charles Mingus, Freddie Redd, Teddy Edwards and Roy Eldridge to name a few.

He also spent a number of years as a sideman with Oscar Pettiford, and working with Charlie Rouse and Julius Watkins forming the Jazz Modes in 1957. After two years the trio split up and Ron signed on with Les McCann prior to moving to Los Angeles in 1962. It was there he cut his debut album as a leader titled “Love Lifted Me” on the Pacifica label.

In addition to playing behind Groove Holmes, Zoot Sims, Carmell Jones and Joe Castro, Ron also toured with Roland Kirk’s “Jazz and People’s Movement”, spent a number of years in Paris working with Hazel Scott, taught music for the U.S. Embassy and in 1976 he cut “Vout Etes Swing!” for the Catalyst label.

Upon returning to New York, Jefferson hosted the cable TV series Miles Ahead with fellow musician John Lewis. Despite a steady work schedule, he never attained the visibility or renown of many of his contemporaries, and after a brief illness drummer Ron Jefferson died in Richmond, Virginia on May 7, 2007.

More Posts: drums

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Juini Booth was born Arthur Edward Booth on February 12, 1948 in Buffalo, New York. He began playing piano at about age eight, and switched to bass at 12. He worked with Chuck Mangione in his hometown before moving to New York City around 1966, where he played with Eddie Harris, Art Blakey, Sonny Simmons, Marzette Watts, Freddie Hubbard and Shelley Manne out in Hollywood through the end of the decade.

In the 70s Juini performed with Erroll Garner, Gary Bartz, Charles Brown, Tony Williams and McCoy Tyner and recorded with Larry Young, and with Takehiro Honda and Masabumi Kikuchi during a 1974 tour of Tokyo. He would spend a short period with Hamiett Bluiett, then resettle in Buffalo but worked with Chico Hamilton in Los Angeles and Junior Cook in New York. By the late 70s he played with Elvin Jones and Charles Tolliver.

From 1980 on, he played with Ernie Krivda in Cleveland, as well as locally in Buffalo. He recorded freelance with Beaver Harris, Steve Grossman, Joe Chambers, and Sun Ra among others and currently lives and works in New York City.

Double and electric bassist Juini Booth died on July 11, 2021 at the age of 73.

More Posts: bass