Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Thomas S. McIntosh was born February 6, 1927 in Baltimore, Maryland and studied at the Peabody Conservatory. During his time in the Army band he played trombone, followed by a move to New York in 1956 where he played with Lee Morgan, Roland Kirk, James Moody, Art Farmer and Benny Golson. During this period he also graduated from Julliard.

By 1961 he was composing “The Day After” for trumpeter Howard McGhee and two years later for Dizzy Gillespie’s “Something Old, Something New” album. The following year his composition “Whose Child Are You?” was performed by the New York Jazz Sextet, of which he was a member.

Working with Thad Jones and Mel Lewis in the late Sixties, as a leader McIntosh recorded Manhattan Serenade and worked with earl Coleman, Jerome Richardson, Billy Taylor, Frank Foster, Eddie Williams, Gene Bertoncini, Bobby Thomas and Reggie Workman. He arrange for Bobby Timmons and Milt Jackson, working as a sideman with the later and also Oliver Nelson and Shirley Scott.

Tom gave up jazz and moved to Los Angeles and began a long and successful career composing for film and television writing music for such films as The Learning Tree, Soul Soldier, Shaft’s Big Score, Slither, A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But A Sandwich and John Handy. In 2008 he was honored by the National Endowment for the Arts as a Jazz Master. Trombonist and composer Tom McIntosh passed away in his sleep at age 84 on July 26, 2017.

More Posts: trombone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Dick Nash: The Trombone Voice Behind Hollywood’s Golden AgeRichard Taylor Nash was born on January 26, 1928, in Boston, Massachusetts, and discovered brass instruments at age ten but it was tragedy that would deepen his commitment to music. After his parents’ death, while living in boarding school, the young Nash threw himself into trumpet and bugle, finding solace and purpose in the discipline and beauty of making music. What began as comfort became calling.

From Big Bands to the Studio

Nash’s first professional work came in 1947 with bands like Tex Beneke’s popular ensemble, a solid apprenticeship with a name bandleader. After serving in the Army, where he continued playing, he joined Billy May’s swinging outfit, gaining experience in the competitive world of post-war big bands.

But Nash’s real destiny was waiting in Los Angeles, where he would become one of the most sought-after studio musicians in the entertainment capital of the world. When producers needed a trombonist who could nail it on the first take, who could read anything, who could deliver both technical perfection and emotional depth, they called Dick Nash.

Mancini’s Secret Weapon

Nash became the favorite trombonist of composer and conductor Henry Mancini, and if you know Mancini’s work, you understand the honor that represents. Mancini wrote sophisticated, jazz-inflected scores that required musicians who could swing, play with taste, and capture specific moods with just a few perfectly placed notes.

Nash was the featured trombone soloist on several iconic Mancini soundtracks: the cool, late-night jazz of Mr. Lucky and Peter Gunn, the exotic adventure of Hatari!, the wistful romance of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and the achingly beautiful melancholy of The Days of Wine and Roses.

If you’ve ever heard that gorgeous trombone solo floating over “Moon River” or punctuating the Peter Gunn theme, that’s Dick Nash—his sound became part of America’s collective musical memory, even if most listeners never knew his name.

Equally at Home in Jazz

But Nash wasn’t just a studio musician grinding out commercial work. By 1959, he was playing bass trombone on saxophonist Art Pepper’s brilliant Art Pepper + Eleven: Modern Jazz Classics session—a challenging, ambitious album that showcased Nash’s ability to function in pure jazz settings alongside one of the West Coast’s most intense improvisers.

A Who’s Who of Collaborations

Over the course of his career, Nash remained predominantly associated with swing and big band genres, but his résumé reads like a directory of 20th-century popular music greatness. Besides working on countless film scores, the trombonist performed and recorded with Quincy Jones, Ella Fitzgerald, Harry James, Count Basie, Oscar Peterson, Louie Bellson, Nat King Cole, Mel Tormé, June Christy, Stan Kenton, Les Brown, Don Ellis, Jimmy Witherspoon, Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, Peggy Lee, Erroll Garner, Anita O’Day, Teresa Brewer, Randy Crawford, The Manhattan Transfer, Sonny Criss… and the list goes on.

The Ultimate Professional

Think about that range: from Basie’s driving swing to Sinatra’s intimate balladry, from Kenton’s progressive big band experiments to Ellis’ avant-garde explorations, from pop sessions to pure jazz dates. Nash could do it all, and do it with the kind of musicality that elevated everything he touched.

The Invisible Artist

Dick Nash represents a particular kind of musical excellence that often goes unrecognized: the studio musician who serves the music rather than their own ego, who makes everyone around them sound better, whose artistry is heard by millions but whose name remains known primarily to fellow musicians and serious fans.

He didn’t need the spotlight. He was the light—illuminating countless recordings, soundtracks, and live performances with his warm tone, impeccable technique, and deep musicality.

From a grieving boy in boarding school finding comfort in a bugle to becoming Henry Mancini’s go-to trombonist and one of the most recorded musicians in American history, Dick Nash’s journey reminds us that sometimes the greatest artists are the ones who help others shine.

And if you’ve ever been moved by a film score, charmed by a classic pop recording, or thrilled by a big band arrangement, there’s a good chance Dick Nash’s trombone was part of what made you feel that way—even if you never knew it.

More Posts: trombone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Juan Tizol: The Puerto Rican Trombonist Who Gave Duke Ellington “Caravan”

Imagine stowing away on a ship to chase your musical dreams, then ending up writing some of the most iconic compositions in jazz history. That’s not fiction—that’s Juan Tizol’s extraordinary story.

A Musical Education in Puerto Rico

Born January 22, 1900, in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, Tizol grew up surrounded by music in a family where it was taken seriously. He started on violin but quickly switched to valve trombone, the instrument that would become his distinctive voice. His uncle Manuel Tizol, music director of the San Juan symphony, became his primary teacher, and young Juan soaked up everything—classical technique, ensemble discipline, professional standards. He played in his uncle’s band and gained invaluable experience performing with local operas, ballets, and dance groups. This was a classical education, Puerto Rican style. Tizol wasn’t learning jazz yet—he was learning music, period.

A Dangerous Leap of Faith

Then came 1920 and a decision that would change everything: Tizol joined a band heading to Washington, D.C. The catch? They traveled as stowaways on a ship, risking everything for the chance to play music in America.

Once they arrived safely, the group set up shop at the Howard Theater, one of Washington’s premier African American venues, playing for touring shows and silent movies while occasionally working small jazz and dance gigs on the side. It was at the Howard that Juan first crossed paths with a young Duke Ellington, who was just beginning to make a name for himself.

Joining the Duke Ellington Orchestra

Summer 1929 brought the call that every jazz musician dreams of—Duke wanted him in the band. Tizol became the fifth voice in Ellington’s brass section, and suddenly the maestro had entirely new compositional possibilities. Now he could write for trombones as an actual section instead of just doubling the trumpets. Tizol’s rich, warm valve trombone tone also blended beautifully with the saxophones, often carrying lead melodies that gave Ellington’s sophisticated arrangements their distinctive color and texture.

More Than Just a Sideman

But Tizol wasn’t just a player—he was essential to the band’s daily operation, meticulously copying parts from Ellington’s scores (no small task in the pre-Xerox era) and contributing his own remarkable compositions.

And what compositions! “Caravan” and “Perdido” are timeless jazz standards that musicians still play today, nearly a century later. Both have been recorded hundreds of times and have become part of the permanent jazz repertoire. Tizol also brought explicit Latin influences into the Ellington sound with pieces like “Moonlight Fiesta,” “Jubilesta,” and “Conga Brava,” adding rhythmic spice and exotic colors that made the band’s already rich palette even more distinctive.

California Calling

In 1944, Tizol made a difficult decision—he left Ellington to join Harry James’ Orchestra in Los Angeles. The reason was simple and human: he wanted more stable work and more time with his wife. The constant touring with Duke was glamorous but exhausting.

He returned to Ellington in 1951, then back to James two years later, spending most of his remaining career on the West Coast. There he worked with James’ popular orchestra, contributed to Nelson Riddle’s elegant arrangements, and appeared on the Nat King Cole television show, bringing his warm sound to America’s living rooms.

After one more brief reunion with Ellington in the 1960s—because that musical connection never really disappears—Tizol eventually retired in Los Angeles, where he passed away on April 23, 1984, in Inglewood, California.

A Legacy Beyond Borders

From stowaway to standard-bearer, Juan Tizol’s journey reminds us that jazz has always been an international language—and sometimes the most quintessentially “American” sounds come from somewhere else entirely.

Every time a band plays “Caravan,” with its mysterious, exotic melody suggesting desert caravans and distant lands, they’re playing Juan Tizol’s vision. Not bad for a kid from Puerto Rico who risked everything to follow the music north.

More Posts: trombone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Phil Wilson: The Trombonist Who Turned a Challenge Into a Triumph

Here’s a story that proves sometimes the detours life throws at you lead exactly where you’re meant to be.

An Unexpected Path to Music

Born Phillips Elder Wilson, Jr. on January 19, 1937, in Belmont, Massachusetts, young Phil started out on piano like so many kids do. But when teachers noticed he had a mild form of dyslexia, they suggested switching to trombone—an instrument where reading music might come easier for him, where the physical act of playing could help compensate for the visual challenges. That simple suggestion changed everything.

Not only did the condition fail to slow him down, but by age fifteen Wilson had already turned professional. Talk about finding your calling early. What could have been an obstacle became a launching pad.

Making His Mark on the Big Band Scene

The late 1950s saw him playing with Herb Pomeroy’s respected Boston-based band (1955-57), then hitting the road with the legendary Dorsey Brothers. The 1960s brought him into Woody Herman’s celebrated Thundering Herd, and soon he was writing sophisticated arrangements for the explosive Buddy Rich. Wilson wasn’t just playing trombone in these organizations—he was actively shaping their sound, contributing ideas, pushing boundaries.

Leader and Educator

By the mid-1960s, he’d begun recording as a leader, eventually releasing fourteen albums over his career that showcased his warm tone, technical command, and compositional vision. But perhaps his most lasting impact has been as an educator—and this is where Wilson’s story becomes truly inspiring.

When Wilson joined the Berklee College of Music faculty in 1965, he didn’t just teach private lessons and cash his checks. He built something special. The ensemble he formed became one of the most respected college jazz bands in the country, a proving ground for countless future professionals who’ve gone on to shape contemporary jazz. For students, playing in Wilson’s ensemble wasn’t just an educational experience—it was a rite of passage.

His influence extended beyond Berklee, too, as he served as chairman of the jazz division at the New England Conservatory of Music, helping shape curriculum and philosophy at two of America’s most important jazz institutions.

Still Going Strong

Decades later, Phil Wilson continues doing what he’s always done: composing new works, performing when the spirit moves him, and teaching the next generation with the same passion and patience that defined his early years in the classroom.

The Power of Adaptation

From a kid who struggled with reading to a master trombonist, composer, arranger, and educator who’s fundamentally shaped American jazz education—that’s not just overcoming obstacles. That’s redefining what’s possible. That’s proving that sometimes what looks like a limitation is actually an invitation to find your true voice.

Sometimes the instrument chooses you. And sometimes, when you let it, it changes not just your life but the lives of thousands of students who pass through your classroom over half a century.

That’s Phil Wilson’s legacy: a career built not despite a challenge, but because he and his teachers found the perfect creative response to it.

More Posts: trombone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

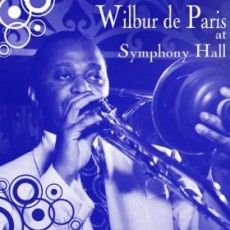

Wilbur de Paris: From Plantation Shows to the World Stage

Born on January 11, 1900, in Crawfordsville, Indiana, Wilbur de Paris grew up in a household where music wasn’t just entertainment—it was the family business. His father was a multi-instrumentalist who played trombone, banjo, and guitar, and he had big plans for his musically gifted son.

A Childhood on the Road

By the autumn of 1906, when little Wilbur was just five years old, he had already begun learning the alto saxophone. A year later—at an age when most children are still in elementary school—he was working professionally in his father’s plantation shows, crisscrossing the South on the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) circuit. It was a grueling apprenticeship, but one that would serve him well.

The Moment Everything Changed

At sixteen, while performing in a summer show at the Lyric Theatre, de Paris heard jazz for the first time. The experience was transformative. Soon after, while playing saxophone at the legendary Tom Anderson’s Cafe with A. J. Piron’s band, he met a young trumpet player who would change music history: Louis Armstrong. These encounters lit a fire that would burn for the rest of de Paris’s life.

Building His Own Sound

After high school, de Paris continued working with his father before joining various traveling shows in the East. In the early 1920s, he made his way to Philadelphia and took a bold step—forming his first band, Wilbur de Paris and his Cottonpickers. He was building something of his own.

Surviving the Crash, Finding New York

When the Wall Street Crash of 1929 devastated the entertainment industry, de Paris disbanded his second group and made the move that would define his career: he headed to New York City. There, he spent years playing and recording with jazz royalty, absorbing every influence and honing his distinctive approach to the trombone.

The New New Orleans Sound

In the late 1940s, Wilbur teamed up with his brother Sidney to launch an ambitious project: a band called New New Orleans Jazz. The ensemble featured legendary figures including Jelly Roll Morton, drummer Zutty Singleton, and clarinetist Omer Simeon. But this wasn’t mere nostalgia—de Paris had a vision of blending traditional New Orleans jazz with the sophisticated swing that had emerged in the intervening decades.

The concept caught fire. Throughout the 1950s, the band became a beloved institution in New York City, recorded extensively, and toured the world, bringing their unique fusion of old and new to audiences everywhere.

A Legacy of Innovation

Wilbur de Paris passed away on January 3, 1973—just eight days before what would have been his 73rd birthday. He left behind a legacy that proved you could honor tradition while pushing it forward, that New Orleans jazz and swing weren’t competing styles but complementary voices in the grand conversation of American music.

From a five-year-old on the TOBA circuit to an internationally recognized bandleader, Wilbur de Paris lived the full arc of jazz’s golden age—and helped shape its sound every step of the way.

More Posts: bandleader,history,instrumental,jazz,music,trombone