Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Wilbur C. Sweatman was born in Brunswick, Missouri on February 7, 1882 and started playing violin but took up clarinet. He toured with circus bands in the late 1890s, briefly played with the bands of W.C. Handy and Mahara’s Minstrels before organizing his own dance band in Minneapolis, Minnesota by late 1902.

It was there that Sweatman made his first recordings on phonograph cylinders in 1903 for a local music store. These included what is reputed to have been the first recorded version of Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag”; however, no copies of these are known to exist today. By 1908, Sweatman was in Chicago as bandleader at the Grand Theater where he attracted notice and in a 1910 article was referred to his nickname, “Sensational Swet.”

By 1911, he had moved to the vaudeville circuit full-time, developing a successful act of playing three clarinets at once, went on to write a number of rags including his most famous “Down Home Rag”. He would move back to New York, tour major vaudeville circuits, befriend Scott Joplin and become his executor, record for Emerson Records, and the first Black to make recordings as Jazz or “Jass” as it was known then and one of the first to join ASCAP, and several notable musicians passed through his band, including Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Cozy Cole.

Wilbur Sweatman, ragtime and Dixieland jazz composer, bandleader and clarinetist who continue to record for Gennett, Edison, Grey Gull and Victor record labels, passed away in New York City on March 9, 1961.

More Posts: clarinet

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Bill Easley: A Life Lived Through Every Era of Modern Jazz

Some musicians pass through jazz history. Bill Easley has lived it—from Harlem jam sessions to Stax Records, from Arctic military bands to Broadway’s brightest lights.

A Prodigy from Upstate New York

Born January 13, 1946, in Orleans, New York, Easley was already a working professional by age thirteen, gigging with his parents and absorbing the craft from the inside. When he arrived in New York City in 1964, he dove straight into the deep end—studying part-time at the legendary Juilliard School while simultaneously earning his real education in Harlem’s uptown jazz clubs, learning directly from the masters who made the music breathe.

An Unexpected Arctic Interlude

Then came an unexpected detour: the draft. Suddenly, Easley found himself stationed in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the 9th Army Band. It wasn’t exactly 52nd Street, but as any true musician knows, you make music wherever you are—even when surrounded by snow instead of skyscrapers.

The Real Education Begins

Back in action by the late ’60s, Easley was playing the legendary rooms that defined the era—Minton’s Playhouse, the Plugged Nickel, The Jazz Workshop, The Hurricane—standing shoulder to shoulder with George Benson. These weren’t just gigs; they were nightly master classes in jazz history happening in real time, each set a conversation with the greats.

Memphis Soul and Stax Swagger

The ’70s brought a southern migration to Memphis, where Easley entered Isaac Hayes’ orbit, laying down tracks at the iconic Stax and Hi Records—the studios where soul music was being redefined. Even while pursuing his formal education at Memphis State University, he was out there every night with big bands and show bands, whatever was swinging.

Then came the gig that changes everything for any jazz musician: touring with the Duke Ellington Orchestra under Mercer Ellington in the mid-’70s. To play that book, to carry that legacy—it’s a responsibility and an honor few ever experience.

The Great White Way Calls

By 1980, Broadway beckoned, and Easley answered. His theater credits read like a greatest-hits compilation: Sophisticated Ladies, The Wiz, Black and Blue, Jelly’s Last Jam, Fosse—the shows that defined an era of musical theater and kept the jazz tradition alive on the world’s most famous stages.

Never Just a Pit Musician

But here’s the thing about Bill Easley: he never stopped being a jazz cat. Between curtain calls, he was in recording studios with pianists Sir Roland Hanna and Mulgrew Miller, organists Jimmy McGriff and Jimmy Smith, vocalist Ruth Brown, and drummers Grady Tate and Billy Higgins. He recorded for respected labels like Sunnyside and Milestone, keeping one foot firmly planted in the jazz tradition even as the other tapped out Broadway rhythms.

Master of Many Voices

Saxophone, flute, clarinet—Easley commands them all with the hard-won wisdom of someone who’s witnessed every chapter of modern jazz unfold firsthand. From bebop to soul jazz, from Broadway pits to intimate club dates, he’s been there, absorbed it, and made it part of his musical DNA.

Still Writing the Story

And the best part? Bill Easley is still out there, still playing, still adding new chapters to a story that now spans six decades and counting. In a world obsessed with the next new thing, there’s something deeply reassuring about a musician who has mastered the art of being present—in every era, in every room, in every note.

That’s not just a career. That’s a life lived in service to the music itself.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Haywood Henry: The Baritone Voice Behind a Thousand Hits

Born Frank Haywood Henry on January 10, 1913, in Birmingham, Alabama, this future jazz great started his musical journey on clarinet before discovering his true calling in the rich, resonant tones of the baritone saxophone. Though the baritone became his signature voice, Henry never abandoned the clarinet entirely, keeping both instruments close throughout his remarkable six-decade career.

From College Band to the Big Time

In 1930, Henry joined the Bama State Collegians, getting his first taste of professional music-making. When he returned to the group in 1934, now led by the dynamic Erskine Hawkins, it marked the beginning of a musical partnership that would last into the 1950s. Hawkins’ orchestra became Henry’s proving ground, where his big-toned baritone work became an essential part of the band’s sound.

A Journeyman’s Journey

After his years with Hawkins, Henry became one of those invaluable musicians who could fit into any setting. He worked with guitarist Tiny Grimes, saxophonist Julian Dash, and the Fletcher Henderson Reunion Band. Perhaps most notably, he occasionally substituted for the legendary Harry Carney in Duke Ellington’s Orchestra—a testament to his skill, given that Carney was widely considered the greatest baritone saxophonist in jazz history.

The 1960s found Henry in equally distinguished company: Wilbur DeParis, Max Kaminsky, Snub Mosley, Louis Metcalf, Earl Hines, Sy Oliver, and the New York Jazz Repertory Company all benefited from his steady presence and warm sound.

The Secret Session King

Here’s where Henry’s story takes a fascinating turn: during the 1950s and ’60s, he became one of the anonymous giants of the recording industry, playing on over 1,000 rock and roll records. While teenagers danced to the latest hits, few knew that a Birmingham-born jazz baritone saxophonist was helping create the sound they loved. In the 1970s, he brought that same professionalism to Broadway pit orchestras, proving once again his remarkable versatility.

Coming Full Circle

In 1971, Henry joyfully participated in an Erskine Hawkins reunion ensemble—a chance to reconnect with old friends and relive the glory days. He continued performing well into the 1980s, his passion for music undiminished by age.

A Leader at Last

Though Henry spent most of his career supporting others, he did step forward as a leader on three occasions: recording for Davis Records in 1957, Strand in the early 1960s, and finally Uptown in 1983. These albums offer rare glimpses of Henry unchained—his baritone taking center stage rather than anchoring the ensemble.

A Well-Earned Honor

In 1978, Alabama recognized one of its own when Haywood Henry was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. When he passed away on September 15, 1994, the jazz world lost one of its most reliable, versatile, and underappreciated voices—a master musician who made everyone around him sound better, whether on a jazz bandstand, a rock and roll session, or in a Broadway pit.

Haywood Henry may not be a household name, but his baritone saxophone spoke to millions, often without them ever knowing it. That’s the mark of a true professional.

More Posts: clarinet,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Joe Marsala: A Clarinet Voice That Bridged Two Eras

Born in the vibrant jazz landscape of Chicago on January 4, 1907, Joe Marsala picked up the clarinet as a young boy and never looked back. What emerged was a distinctive voice—one that would help shape the sound of American music across multiple decades.

Beyond Dixieland

While Marsala came of age during the big band era and shared stages with traditional “Dixieland” musicians, his musical vision reached far beyond convention. His playing was richer, more graceful, and decidedly more adventurous than many of his contemporaries—a style he credited largely to the influence of the masterful Jimmy Noone.

As a bandleader, Marsala helmed ensembles with memorable names like “His Chosen Seven” and “His Delta Four.” He had an eye for talent, too: he was among the first leaders to recognize the explosive potential of a young drummer named Buddy Rich. Throughout his career, Marsala collaborated with an impressive roster of musicians including Joe Buskin, Jack Lemaire, Carmen Mastren, and even the legendary Etta James.

A Pioneer for Integration

Beyond his musical contributions, Marsala stood on the right side of history. During the 1940s, he was at the forefront of breaking down racial barriers in jazz, working alongside Dizzy Gillespie and other Black musicians at a time when such collaborations required both courage and conviction.

Reinvention and Resilience

As bebop swept through the jazz world, Marsala faced a harsh reality: clarinetists were increasingly sidelined in the new sound. Work became scarce, both on stage and in the studio. But rather than fade away, Marsala reinvented himself.

He turned his creative energies to songwriting, crafting what we now call classic pop standards. His compositions found their way to two of the era’s biggest voices: Frank Sinatra and Patti Page. Songs like “Don’t Cry, Joe” and “And So To Sleep Again” showcased a different side of his artistry—proof that a true musician can adapt without losing their soul.

Despite battling chronic colitis throughout his later years, Marsala continued contributing to American music until his passing on March 4, 1978, in Santa Barbara, California. His legacy remains a testament to versatility, courage, and the enduring power of a clarinet played with grace and conviction.

More Posts: bandleader,clarinet,history,instrumental,jazz,music

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

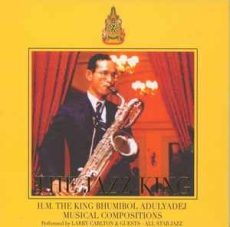

Bhumibol Adulyadej was born on December 5, 1927 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, however, the family moved to Bangkok, Thailand where she briefly attended Mater Dei school. In 1933 his mother took the family to Switzerland, where he continued his education at the École nouvelle de la Suisse romande in Lausanne. In 1934 he was given his first camera, which ignited his lifelong enthusiasm for photography.

Before he became King of Thailand, titled Rama IX, in 1942, Bhumibol became a jazz enthusiast, and started to play the saxophone, a passion that he kept throughout his life. He received his high-school diploma with a major in French literature, Latin, and Greek from the Gymnase Classique Cantonal de Lausanne, and by 1945 had begun studying sciences at the University of Lausanne, when World War II ended and the family was able to return to Thailand.

Adulyadej became an accomplished jazz baritone saxophone player and composer, playing Dixieland and New Orleans jazz. He also played the clarinet, trumpet, guitar, and piano. It is widely believed that his father may have inspired his passion for artistic pursuits at an early age. Initially focusing on classical music exclusively for two years but eventually switched to jazz since it allowed him to improvise more freely. It was during this time that he decided to specialize in wind instruments, especially the saxophone and clarinet. By 18 he started composing his own music with the first being Candlelight Blues.

He continued to compose even during his reign following his coronation in 1946. Bhumibol performed with Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Benny Goodman, Stan Getz, Lionel Hampton, and Benny Carter. Throughout his life, Bhumibol wrote a total of 49 compositions, much of it is jazz swing but he also composed marches, waltzes, and Thai patriotic songs.

He initially received general music training privately while he was studying in Switzerland, but his older brother, then King Ananda Mahidol, who had bought a saxophone, sent Bhumibol in his place. King Ananda would later join him on the clarinet. On his permanent return to Thailand in 1950, he started a jazz band, Lay Kram, whom he performed with on a radio station he started at his palace. The band grew, being renamed the Au Sau Wan Suk Band and he performed with them live on Friday evenings, occasionally taking telephoned requests.

Many bands such as Les Brown and His Band of Renown, Claude Bolling Big Band, and Preservation Hall Jazz Band recorded some of his compositions and can still be heard in Thailand. A 1996 documentary, Gitarajan, was made about his music. Adulyadej still played music with his Au Sau Wan Suk Band in later years, but was rarely heard in public. In 1964, Bhumibol became the 23rd person to receive the Certificate of Bestowal of Honorary Membership on behalf of Vienna’s University of Music and Performing Arts.

Baritone saxophonist, clarinetist, trumpeter, guitarist, pianist and composer and King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who reigned for 70 years and 126 days and is the longest of any Thai monarch, died on October 13, 2016 in Bangkok, Thailand.

More Posts: bandleader,clarinet,composer,guitar,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano,saxophone,trumpet