Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Jean-Paul Maunick was born February 19, 1957 in Mauritius to poet Edouard Maunick. At the age of nine his family moved to the United Kingdom and learning to play the guitar began his journey in music.

A founding member of the group Light of the World, Maunick formed the British acid jazz band Incognito in 1979 and released his debut album “Jazz Funk” in 1981. Bluey, as he is known to most, has fused funk, R&B, Brazilians rhythms and soul into a sound that has captured and kept the world’s attention. In addition to releasing fourteen studio albums as well as several live albums, remix albums and compilation albums.

His group dynamic has changed over the years as he has brought singers Jocelyn Brown, Carleen Anderson, Tony Momrelle, Imaani, Maysa Leak Kelli Sae of Count Basic and Joy Malcom to take the lead vocal position. His record production credits include artists such as Paul Weller, George Benson, Maxi Priest, and Terry Callier, having also collaborated with Stevie Wonder.

Guitarist, bandleader, composer and record producer Jean Paul Maunick, better known as Bluey, continues to explore new directions in music performing and touring worldwide.

More Posts: guitar

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

De De Pierce was born Joseph De Lacroix Pierce on February 18, 1904 in New Orleans, Louisiana. A trumpeter and cornetist, his first gig was with Arnold Dupas in 1924. During his time playing in New Orleans nightclubs he met Billie Pierce, who became his wife as well as a musical companion. They took residence as the house band at the Luthjens Dance Hall from the 1930s through the 1950s.

They released several albums together but stopped performing in the middle of the 1950s due to illness, which left De De Pierce blind. By 1959 they had returned to performing with De De touring with Ida Cox and playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band before further health problems ended his career.

On November 23, 1973, De De Pierce, best remembered for the songs “Peanut Vendor” and “Dippermouth Blues”, passed away at the age of 69.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

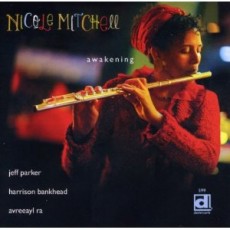

Nicole Mitchell was born on February 17, 1967 in Syracuse, New York where she was raised until age eight, when her family moved to Anaheim, California. She began with piano and viola in the fourth grade; however, she was classically trained in flute and played in youth orchestras as a teenager. Her initial college major in math was superseded by jazz while in college and took to busking in the streets playing jazz flute. After two years at the University of California, San Diego, in 1987 she transferred to Oberlin College.

In 1990 a move to Chicago saw her playing once again on the streets and working for third World Press and meeting members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Mitchell soon started playing with the all-women ensemble Samana under the AACM umbrella. Over the next several years she moved to New Orleans, became a mother, returned to school earning her BA and Masters, met and extensively began playing with Hamid Drake, then worked with saxophonist David Boykin prior to starting her group the Black Earth Ensemble” and co-hosting the Avant-Garde Jazz Jam Sessions in Chicago.

Releasing her debut album “Vision Quest” in 2001, she has been named “Rising Star” flautist for 2004 -2006 by Down Beat and by Down Beat International Critics Poll in 2010 & 2011. As an educator, Nicole has taught at Northern Illinois, Chicago State, Northeastern Illinois University, Wheaton College and the University of Illinois at Chicago; and has been co-president of the AACM since 2006.

More Posts: flute

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

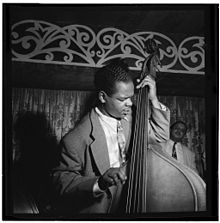

Alvin “Junior” Raglin was born March 16, 1917 and started out on guitar but had picked up bass by the mid-1930s. He played with Eugene Coy from 1938 to 1941 in Oregon and then joined duke Ellington’s Orchestra, replacing Jimmy Blanton. Junior remained in Ellington’s employ from 1941 to 1945.

After leaving Ellington’s orchestra, Raglin led his own quartet, and also played with Dave Rivera, Ella Fitzgerald and Al Hibbler. He returned to play with Ellington again briefly in 1946 and 1955, however he fell ill in the late 1940s and quit performing.

Junior Raglin, swing jazz double bassist, died on November 10, 1955 at age 38, never having the opportunity to record as a leader.

More Posts: bass

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Walter “Rosetta” Fuller was born on February 15, 1910 in Dyersburg, Tennessee, first learning to play the mellophone as a child before settling on trumpet. He played in a traveling medicine show from age 14, then played with Sammy Stewart in the late 1920s.

Fuller In 1930 he moved to Chicago and played with Irene Eadie and Her Vogue Vagabonds. In 1931 he began a longtime partnership with Earl Hines, remaining with him until 1937, when he left to join Horace Henderson’s ensemble. After a year with Henderson he returned to Hines’ band but once again left Hines in 1940 to form his own band, playing at the Grand Terrace in Chicago and the Radio Room in Los Angeles. Among his sidemen were Rozelle Claxton, Quinn Wilson, Omer Simeon and Gene Ammons.

Fuller got the nickname “Rosetta” based on his singing on the 1934 Hines recording of the song of the same name. He would lead bands on the West Coast for over a decade and play as a sideman for many years afterward. On April 20, 2003 trumpeter and vocalist Walter Fuller passed away in San Diego, California.