Daily Dose Of Jazz…

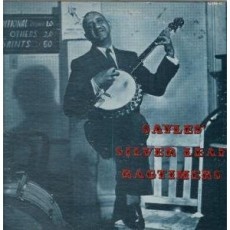

Emanuel Sayles: The Banjoist Who Followed the Music HomeEmanuel Sayles was born on January 31, 1907, in Pensacola, Florida, and began his musical education in the classical tradition, playing violin and viola as a child. But the jazz spirit was calling, and Sayles answered by teaching himself banjo and guitar, the instruments that would define his career and connect him to the early New Orleans jazz tradition.

Following the Music to New Orleans

After high school, Sayles made the pilgrimage that so many musicians made: he relocated to New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, where he joined William Ridgely’s Tuxedo Orchestra, a prestigious gig that put him in the center of the city’s vibrant music scene.

What followed was a classic New Orleans apprenticeship: Sayles worked with the legendary pianist Fate Marable, violinist Armand Piron, and trumpeter Sidney Desvigne on Mississippi riverboats, those floating conservatories where musicians learned to swing, read charts, and play for dancers night after night. The riverboat gigs were grueling but invaluable, connecting Sayles to the earliest generations of jazz musicians and teaching him the repertoire that would sustain him for decades.

Making History in Chicago

In 1929, Sayles participated in recordings with the Jones-Collins Astoria Hot Eight—sessions that captured the raw, collective improvisation style of early New Orleans jazz before it became codified and nostalgic. These recordings remain treasured documents of a transitional moment in jazz history.

By 1933, Sayles had moved to Chicago, where he led his own group and became a sought-after accompanist on blues and jazz recordings, working frequently with the great barrelhouse pianist Roosevelt Sykes and others. Chicago in the 1930s was electric with blues and swing, and Sayles’ banjo added that distinctive rhythmic drive that made everything move.

Always Returning to New Orleans

In 1949, Sayles returned to New Orleans, the first of several homecomings, and joined forces with clarinetist George Lewis, one of the leading voices in the New Orleans traditional jazz revival. In 1963-64, he toured Japan with Lewis, bringing authentic New Orleans jazz to audiences halfway around the world who were hungry to hear the music in its original form.

Back in New Orleans, he played with the beloved pianist Sweet Emma Barrett, then traveled to Cleveland in 1960 to work with trumpeter Punch Miller. From 1965 to 1967, he was back in Chicago playing in the house band at the Jazz Ltd. Club, one of the premier traditional jazz venues in the country.

Preservation Hall and the Final Chapter

Returning once more to New Orleans in 1968, Sayles found his spiritual home with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, the ensemble dedicated to keeping the traditional New Orleans sound alive for new generations. Preservation Hall wasn’t just a venue, it was a mission, and Sayles was perfectly suited to be part of it.

Documenting the Tradition

Sayles recorded prolifically as a sideman with cornetist Peter Bocage, trumpeter Kid Thomas Valentine, pianist Earl Hines, and drummer Louis Cottrell, each session a masterclass in the early New Orleans ensemble style. As a leader, he recorded extensively throughout the 1960s for GHB, Nobility, Dixie, and Big Lou record labels, ensuring that his particular approach to the banjo, rhythmically propulsive, harmonically sophisticated, never overplaying, would be preserved for future students of the tradition.

The Unsung Rhythm Master

Emanuel Sayles passed away on October 5, 1986, having spent nearly eight decades playing the music he loved. As a master banjoist, he represented something increasingly rare: a direct connection to the earliest days of jazz, when the banjo was king of the rhythm section and New Orleans was the only place the music existed.

Why His Story Matters

Sayles’ career is a reminder that jazz history isn’t just about the innovators who pushed the music forward, it’s also about the dedicated musicians who preserved what came before, who understood that the old New Orleans collective improvisation style had value and beauty that shouldn’t be lost in the rush toward bebop and beyond.

Every time he returned to New Orleans—and he kept returning, Sayles was affirming that the music’s roots mattered, that there was wisdom in the way the old-timers played, that the banjo had a place even as guitars became dominant. From Pensacola to riverboats to Chicago clubs to Preservation Hall, Emanuel Sayles followed the music wherever it led and always, eventually, back home to New Orleans, where it all began.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

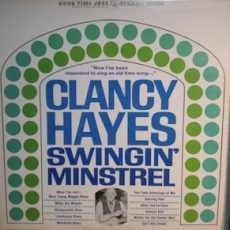

Clancy Hayes was born Clarence Leonard Hayes on November 14, 1908 in Caney, Kansas. As a child he learned the drums before switching to guitar and banjo.

Being part of a vaudeville troupe in the Midwest after 1923, Hayes lived in San Francisco from 1927. He became more popular in the 1930s through radio and club performances. From 1938 to 1940 he played in a big band led by Lu Watters, after which he spent a decade with the Yerba Buena Jazz Band, playing rhythm banjo and, on occasion, drums.

Spending almost all of the 1950s singing with Bob Scobey’s band, in the 1960s he led his own bands, which also recorded for various labels. Hayes played with the Firehouse Five Plus Two, Turk Murphy, and a group that evolved into the World’s Greatest Jazz Band. As a vocalist he was noted for his straightforward singing of ballads and his flamboyant delivery of livelier songs.

Banjoist and vocalist Clancy Hayes, who recorded eleven albums as a leader and six with Bob Scobey, died in San Francisco, California on March 13, 1972.

More Posts: bandleader,banjo,history,instrumental,jazz,music,vocal

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

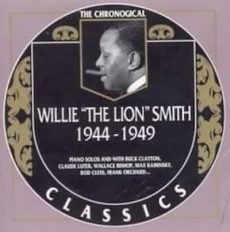

Frank Orchard was born on September 21, 1914 in Chicago, Illinois. He studied at Juilliard from 1932-33 and performed for a year with Stanley Melba’s band, but then worked outside of music altogether, mostly as a salesman until 1941.

Orchard became a part of the New York Dixieland scene in the 1940s, working with Jimmy McPartland, Jimmy Dorsey, Louis Armstrong, Bobby Hackett, Max Kaminsky, Wingy Manone, Joe Marsala and the Eddie Condon gang.

The mid-1950s saw Frank’s move to Dayton, Ohio and eventually to St. Louis, Missouri and still playing trombone although out of the spotlight. He never led his own record date and returned to New York in the 1960s. He worked regularly at Jimmy Ryan’s from 1970-71 and with Billy Butterfield in 1979.

Trombonist, violinist, banjoist and tubist Frank Orchard, who also played in the Willie “The Lion” Smith band with Jack Lesberg, Mac McGrath, Max Kaminsky, Rod Cless, died December 27, 1983 in Manhattan, New York City, New York.

More Posts: banjo,history,instrumental,jazz,music,trombone,tuba,violin

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

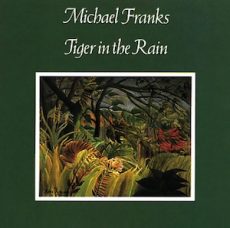

Michael Franks was born September 18, 1944 in La Jolla, California and grew up with two younger sisters. Neither parent was a musician but they loved swing music, and his early influences included Peggy Lee, Nat King Cole, George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and Johnny Mercer. At age 14 he bought his first guitar, a Japanese Marco Polo for $29.95 with six private lessons included. Those lessons were the only music education that he received.

While at University High School in San Diego,California he discovered the poetry of Theodore Roethke with his off-rhymes and hidden meter. He began singing folk-rock, accompanying himself on guitar. Studying English at UCLA, Michael discovered Dave Brubeck, Patti Page, Stan Getz, João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Miles Davis. Never studying music in college or later, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from UCLA in comparative literature in 1966 and a Master of Arts degree from the University of Oregon two years later. He returned to UCLA to teach after a stint in a PhD program in Montreal.

During this time Franks started writing songs, starting with the 1968 antiwar musical Anthems in E-flat and went on to compose music for films. Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee recorded three of his songs, on their album Sonny & Brownie. Franks played guitar, banjo and mandolin on the album and joined them in touring. In 1973, he recorded an eponymous debut album, later reissued as Previously Unavailable.

In 1976 he released his second album The Art of Tea featuring the Crusaders and which saw Franks begin a long relationship with Warner Bros. Records. Subsequent albums came in 1977 and 1978 and through the 1980s. His move to New York City featured more of an East Coast sound on his albums and performance. Since then, Franks has recorded more than 15 albums.

He has recorded with a variety of well-known artists, such as Peggy Lee, Dan Hicks, Patti Austin, Art Garfunkel, Brenda Russell, Claus Ogerman, Joe Sample, and David Sanborn. His songs have been recorded by Shirley Bassey, Kurt Elling, Diana Krall, The Manhattan Transfer, Leo Sidran, Veronica Nunn, Carmen McRae, and Natalie Cole, aming other pop and rock artists.

Vocalist and songwriter Michael Franks, who plays guitar, banjo, mandolin, and cabasa, is still active and working on a new project.

More Posts: banjo,cabasa,guitar,history,instrumental,jazz,mandolin,music,songwriter,vocal

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Clarence Holiday was born Clarence Halliday on July 23, 1898 in Baltimore, Maryland and attended a boys’ school with the banjo player Elmer Snowden. Both of them played banjo with various local jazz bands, including the Eubie Blake band. At the age of 16, he became the unmarried father of Billie Holiday, who was born to 19-year-old Sarah Fagan, but rarely visited them. He moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he was 21 years old.

Holiday played rhythm guitar and banjo as a member of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra from 1928 to 1933. He went on to record the following year with Benny Carter, then Bob Howard in 1935 and worked with Charlie Turner, Louis Metcalf, and the Don Redman Big Band between 193 and 1937.

Exposed to mustard gas while serving in World War I, he later fell ill with a lung disorder while on tour in Texas. Refused treatment at a local hospital when he finally managed to see a doctor, Clarence was only allowed in the Jim Crow ward of the Veterans Hospital. By then pneumonia had set in and without antibiotics, the illness was fatal.

Guitarist and banjoist Clarence Holiday died in Dallas, Texas on March 1, 1937.