Requisites

Steppin’ Out ~ Harold Vick | By Eddie Carter

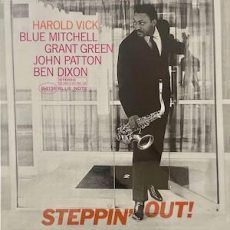

One of the joys of jazz collecting is seeing favorite LPs surface again in the wild and as audiophile albums. This morning’s discussion is a welcome reissue by Harold Vick. Steppin’ Out (Blue Note BLP 4138/BST 84138) was the tenor saxophonist’s debut album and the only one he made for the label as a leader. It was recorded in 1963 and released the same year. For his first effort, Harold’s joined by Blue Mitchell on trumpet, John Patton on organ, Grant Green on guitar, and Ben Dixon on drums. I first heard him on Oh Baby! Patton’s 1965 release with the same lineup. My copy is the 2022 Blue Note Tone Poet Series Stereo audiophile reissue sharing the original catalog number.

Our Miss Brooks is the first of five originals by the leader. It starts with the quintet’s finger-snapping, toe-tapping melody. Harold serves up the first slice of this soulful song; next, the group makes a short bridge into Grant’s tasteful reading. The second bridge leads to John mining a vein of bluesy riches in the finale ahead of the ensemble’s close. Trimmed In Blue steps up the pace for the quintet’s theme. Vick starts the solos with a spirited interpretation, then Mitchell comes behind him to give an exuberant reading. Green replies with a sparkling statement, followed by Patton’s zesty bounce leading to the theme’s reprise.

Laura, by David Raskin and Johnny Mercer, became a jazz standard as the title tune of the 1944 film noir. Blue sits out for the quartet’s hauntingly dreamlike melody. Harold makes a profound impression in the song’s only solo with nostalgic romanticism over the rhythm section’s subtle support into a gorgeous ending. Dotty’s Dream opens Side Two with the quintet in a swinging groove from the opening chorus. Vick gets down to business first, then Mitchell enters for a lively romp. Green responds with a vibrant reading, and Patton’s closing remarks are fueled with comments from both horns into the climax.

The quintet takes a relaxing trip to Vicksville next. The ensemble’s easy-swinging theme starts this comfortable ride into Blue’s smooth-sailing opening statement. Grant builds a perfect solo from simple ideas next. Harold strolls into an exquisite interpretation; then, John concludes with a carefree comment before the closing chorus fades out. The title tune, Steppin’ Out, moves the beat upward for the ensemble’s invigorating melody. Vick lets the listener know they’re in for a treat on the opening statement; then Green follows with an excellent solo. Mitchell comes in for a cheerful reading next, and Patton winds up the session in a festive finale preceding the theme’s return.

Alfred Lion produced the initial session of Steppin’ Out. Rudy Van Gelder was the recording engineer behind the dials. Joe Harley supervised the audiophile reissue, and Kevin Gray mastered it at Cohearent Audio. The front and rear covers are high gloss and gorgeous, with session gatefold photos worthy of hanging in your listening room. The record is pressed on 180-gram audiophile vinyl. The sound quality is quite good despite a bit of harmonic distortion from John Patton’s organ microphone placement as he’s supporting the other musicians. It’s particularly noticeable on Vicksville and Steppin’ Out.

Don’t let that dissuade you from checking out this album on your next vinyl treasure hunt. Steppin’ Out is a solid debut and a great introduction to this underrated, talented tenor saxophonist with wonderful performances by Grant Green, Blue Mitchell, John Patton, and Ben Dixon, keeping the beat efficiently! If you enjoy soulful jazz from the tenor sax with a double dose of the Blues and Hard-Bop, I offer for your consideration, Steppin’ Out by Harold Vick. It’s just right for an evening listening session with your favorite drink in hand!

~ Oh Baby! (Blue Note BLP 4192/BST 84192) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Laura – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2023 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Requisites

My Conception ~ Sonny Clark | By Eddie Carter

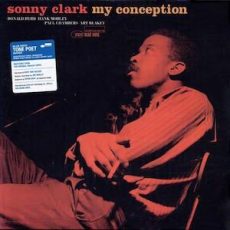

Sonny Clark enters this morning’s spotlight with a 1959 recording session that remained in the vault for two decades. My Conception (Blue Note GXF 3056) is a 1979 release that came out first in Japan and later as a 2000 CD album in the US. Clark was one of the label’s house pianists, recording some of his finest albums as a leader. He also appeared on numerous releases as a sideman. Here, Sonny is leading a stellar quintet in a program of his original tunes. Donald Byrd on trumpet, Hank Mobley on tenor sax, Paul Chambers on bass, and Art Blakey on drums. My copy is the 2021 Blue Note Tone Poet Series Stereo audiophile reissue (BST 22674).

Junka starts with the quintet’s upbeat melody. In the opening reading, Hank gets things going energetically, then Donald makes an impressive appearance. Sonny follows with a high-spirited statement next. Paul delivers a sparkling comment; then Art shares the last spot with the front line preceding the theme’s reprise. Blues Blue starts with the quintet’s danceable beat in the opening chorus. Mobley leads the way with an attractive reading, then Byrd comfortably swings into the next segment. Clark improvises the following message effectively, then Chambers’ inspired bass work comes. Blakey shares the final conversation with both horns ahead of the climax.

There’s nothing minor about the first side finale, Minor Meeting. Art calls the quintet together for their vivacious melody. Donald is off and running in the opening solo, then Hank soars to new heights in the following presentation. Sonny closes with a series of scintillating choruses leading to the finale. Side Two commences with Royal Flush, a toe-tapping medium groove that gets underway with the ensemble’s theme. Mobley goes to work first, followed by Clark’s thoroughly relaxed reading. Byrd is up next and is shown to good advantage, and Chambers takes the final stroll while Blakey keeps the beat into the quintet’s closing chorus.

The group enjoys Some Clark Bars next. After the group establishes the spirited melody, Hank leads the way in a terrific opening solo as tasty as the candy bar. Donald swings as hard in the following interpretation, and Sonny has a great turn in the third reading. Art finishes off the solos in a concise exchange, with the front line before the close. The title tune, My Conception, is a perfect example of Clark’s ability to compose a beautiful ballad. The rhythm section opens with a tender introduction until Mobley emerges to give an elegantly phrased theme and lead solo. Clark takes over to give a wonderfully warm statement, then Byrd concludes with a delicately expressed performance of soulful emotion.

Alfred Lion produced the initial session, and Rudy Van Gelder was the man behind the dials of the recording. Joe Harley supervised the audiophile reissue, and Kevin Gray remastered the album. The front and rear covers are high gloss, with great session photos inside the gatefold. The sound quality is sensational, with an exceptional soundstage. The instruments emerge from your speakers as if you’re in the studio with the musicians while they work. The record was pressed on 180-gram audiophile vinyl, and it’s incredibly quiet until the music starts. If you’re in the mood for Hard-Bop, I invite you to check out My Conception by Sonny Clark the next time you’re out vinyl shopping. Despite being unreleased for so many years, it’s a great album that was well worth the wait and a joy to listen to!

~ My Conception (Blue Note Connoisseur Series 7243 5 22674 2 2) – Source: Discogs.com © 2023 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano

Requisites

Sonny Stitt Blows The Blues | By Eddie Carter

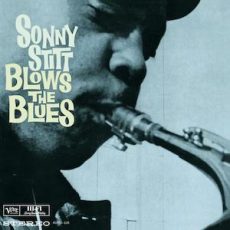

It happened like this; after listening to Bud Powell ’57, I wanted something else to hear while reading. So, I chose another of my mom’s favorite albums that she loved playing while cooking dinner. Sonny Stitt Blows The Blues (Verve Records MG V-8374/MG V6-8374) is an excellent 1960 date culled from two 1959 December sessions. Sonny Stitt was equally fluent on the tenor and baritone sax but is exclusively heard here on the alto sax. He assembled an exceptional rhythm section to join him, Lou Levy on piano, Leroy Vinnegar on bass, and Mel Lewis on drums. My copy is the 1995 Classic Records US Stereo audiophile reissue (Verve Records MG VS-6149).

The opener, Blue Devil Blues, is the first of five tunes by Mr. Stitt. It starts with Mel’s brief introduction; next, Sonny emerges to establish the easygoing melody, then gives an exquisite opening statement. Lou follows with a few flowing lines, and Leroy punctuates the solos with a brief comment. Home Free Blues picks up the pace to a medium beat for Stitt’s alto to lead the quartet in the melody of this happy swinger. He continues laying down strong lines in the first solo that pack a lot of punch. Levy delivers a splendid statement next, then Vinnegar takes a soulful walk ahead of the reprise and ending.

Blue Prelude is a pretty song by Isham Jones that Lou sets in motion with a concise introduction segueing into Sonny’s lightly swinging opening chorus and the song’s only interpretation. The rhythm section lays a lush foundation behind him into the song’s exit. Frankie and Johnny is the story of a couple’s relationship that ends tragically because of the young man’s infidelity. The quartet brings out the best in this old chestnut, with Stitt stating the melody. He then gives an impressive lead solo. In the second statement, Levy gets to the song’s heart; then, Vinnegar has a delightfully light reading ahead of Stitt’s final thoughts.

Side Two starts with Birth of The Blues by Ray Henderson, Lew Brown, and Buddy DeSylva. The quartet opens the song with a mellow theme, then steps aside for Sonny to show off his impeccable chops in the opening statement. Lou is up next with a fine outing, then Leroy has a delightful reading before the climax. A Blues Offering is Sonny’s slow-tempo invitation for the group to relax and take it easy from the start of the melody. Stitt sets the scene thoughtfully and with care first, then Levy responds with tenderness and sincerity in the subsequent interpretation preceding the ensemble’s graceful finale.

Sonny Stitt’s Hymnal Blues is unlike any song I heard when I attended church as a youngster. The foursome starts with a vibrant opening chorus; then, Sonny takes flight and wails in the opening presentation. Lou matches the altoist in the following statement. Leroy wraps it up with a neat finale before the quartet’s closing chorus disappears into nothingness. Vinnegar’s bass introduces After Morning Blues, segueing into Stitt’s sultry theme. The saxophonist has the song’s only reading and turns in a sensuously warm interpretation closely shadowed by the rhythm section’s gorgeous groundwork into the culmination.

The initial producer and the recording engineer of Sonny Stitt Blows The Blues are unknown. However, the sound quality of this Classic Records reissue is fantastic. Bernie Grundman mastered the album, and the instruments emerge from your speakers as if the quartet is playing right before you. The record is pressed on 180 grams of audiophile vinyl and silent until the music starts. If you’re not already a fan of Sonny Stitt, this is an excellent choice to begin your journey into his extensive discography. Every time I hear it, I’m taken back to my childhood and a pleasant memory of my mom. Sonny Stitt Blows The Blues is an enjoyable album from first note to last with a superb supporting cast that highlights the leader’s capabilities as a composer. If you love jazz, I can’t recommend it enough for a spot in your library!

~ Birth of The Blues, Frankie and Johnny – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2023 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Requisites

Bud Powell ‘57 ~ Bud Powell | By Eddie Carter

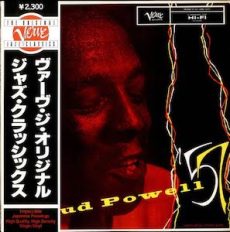

I wanted to hear something soothing after dinner a few nights ago, so I chose one of my favorite records by pianist Bud Powell. This morning’s album from the library comprised three sessions and was initially released as Jazz Original in 1955 and reissued two years later as Bud Powell ’57 (Norgran Records MG N-1098). He’s leading two trios in a program of nine standards. Percy Heath (tracks: A1 to A3), Lloyd Trotman (A4, B2 to B5) on bass, Max Roach (tracks: A1 to A3), and Art Blakey (A4, B2 to B5) on drums. My copy is the 1981 Verve Original Jazz Classics Japanese Mono audiophile reissue (UMV 2571) by Polygram Records.

Deep Night, by Charles E. Henderson and Rudy Vallée, opens the album and is introduced by Bud, then Percy and Max join him to complete the melody. Powell is the song’s only soloist and gives a briskly efficient interpretation complimented by the rhythm section’s compelling understructure leading to the climax. Next, the trio takes on That Old Black Magic by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer. It made its debut in the 1942 film Star Spangled Rhythm. The trio opens the song with a deceptively simple melody before Bud makes a tremendous statement toward the ensemble’s exit.

‘Round Midnight by Thelonious Monk, Cootie Williams, and Bernie Hanighen is one of the most recorded compositions in jazz. Powell opens with a hauntingly beautiful introduction which grows into the trio’s gorgeous melody. Bud has the spotlight and demonstrates delicacy over Percy and Max’s subtle accompaniment ahead of a pretty ending. Thou Swell by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart comes from the 1927 musical, A Connecticut Yankee. The trio picks up their pace to a medium tempo, and Powell leads Trotman and Blakey in the melody. The pianist feeds off their energy and does an excellent job freshening up this old chestnut with a bright performance.

Side Two starts with Like Someone in Love by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke, a solo performance by Bud that premiered in the 1944 film Belle of The Yukon. Powell has the showcase alone here, and right from the song’s entrance, he brings out its warmth of lyricism, tenderness, and sincerity in one of the album’s prettiest performances. Someone To Watch Over Me by George and Ira Gershwin is from the 1926 musical, Oh, Kay! Initially known as a torch song, the group’s interpretation is performed flawlessly, with Powell showing the utmost respect during the melody and in his solo. Trotman and Blakey anchor him politely, preceding the closing chorus.

The tempo moves upward again for Lover Come Back To Me by Sigmund Romberg and Oscar Hammerstein II. It appeared first in the 1928 musical, The New Moon, and it’s a catchy tune beginning with the threesome’s lively opening chorus. Bud opens the song’s only solo at a brisk gallop, complemented by Lloyd and Art leading to the trio’s finale. Tenderly by Walter Gross and Jack Lawrence is an enchanting song about finding love. Powell’s piano makes the introduction which grows into a delicately gentle theme; then Bud reminisces nostalgically in an excellent interpretation preceding the ending.

The album ends with How High The Moon by Morgan Lewis and Nancy Hamilton. It’s an infectious tune with a driving beat that takes off after Bud’s introduction. The pianist swings to Lloyd and Art’s zesty foundation into the theme’s reprise and climax. Norman Granz supervised the initial album, and it’s unknown who was the recording engineer. However, the reissue’s sound quality is excellent, with a stellar soundstage that brings the musicians into your listening room with incredible clarity. The record is pressed on virgin vinyl and silent until the music starts. If you’re in the mood for a relaxing album to enjoy after a long day or week, I offer for your consideration Bud Powell ’57. It’s an endlessly satisfying trio album that I’m sure you’ll enjoy!

~ Jazz Original (Norgran Records MG N-1017) – Source: Discogs.com ~ How High The Moon, Like Someone In Love, Lover Come Back To Me, ‘Round Midnight, Someone To Watch Over Me, Tenderly, That Old Black Magic, Thou Swell – Source: JazzStandards.com ~ Deep Night – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2023 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano

Requisites

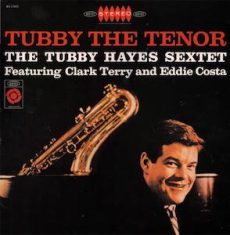

Tubby The Tenor ~ The Tubby Hayes Sextet | By Eddie Carter

Submitted for your approval this morning is a 1962 release by British tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes. The year before, he traveled to the United States for the first time to appear at the Half Note. This week’s album is an excellent studio session recorded at Columbia Studio A during his engagement and initially released in the U.K. as Tubbs in N.Y. Its U.S. counterpart came out the same year and is titled Tubby The Tenor (Epic LA 16023/BA 17023) by The Tubby Hayes Sextet. Hayes is in good company on this date; Clark Terry on trumpet (tracks: A2, B1), Eddie Costa on vibes (tracks: A2, A3, B3), Horace Parlan on piano, George Duvivier on bass, and Dave Bailey on drums. My copy is the 1995 Classic Records U.S. Stereo audiophile reissue sharing the original catalog number.

Side One gets underway with You For Me by Bob Haymes, a quartet feature for Tubby and the rhythm section. The saxophonist sets the scene with an unaccompanied introduction segueing into the foursome’s lively opening chorus. Tubby takes the song’s only solo and gives a swinging interpretation complemented by the trio’s spirited support leading to the closing chorus. Clark Terry’s easy-going blues, A Pint of Bitter, begins with the sextet stating the carefree melody collectively. The trumpeter is up first with a relaxing lead interpretation; then Hayes is equally laid-back on the following statement. Costa comes in next and delivers a leisurely-paced reading; then, Parlan builds a compelling finale ahead of the ending theme.

Airegin by Sonny Rollins opens with the quintet’s brisk theme. Tubby launches the solos with a spirited presentation, then gives way to Eddie, who swings freely in an exciting reading. Horace has the third spot and gives an energetic performance. George walks briskly behind him, ahead of the tenor sax’s and vibraphonist’s concise conversation preceding the reprise and climax. Side Two takes off with Opus Ocean by Clark Terry, a fast-paced thrill ride that moves quickly from the quintet’s collective theme. Hayes is off to the races wailing at top speed in the opening solo, followed by an exhilarating statement from Terry. Parlan turns the heat up on the third reading, and the front line delivers a spirited exchange before the ensemble takes the song out.

The quartet returns to put some fresh clothes on Soon, an old tune from the songbook of George and Ira Gershwin. Horace briefly introduces himself; then Tubby steps up for an excellent melody that flows seamlessly into his impressive lead statement. Horace is next and completes the solos with a festive interpretation until Tubby reappears for the song’s finish. Doxy by Sonny Rollins is misspelled here as Doxie and begins with a relaxing melody led by Hayes and Costa. Hayes is up first and gets into a comfortable groove on the opening statement. Costa comes in next for a pleasant performance, then Parlan takes a nice turn in the third reading. Duvivier wraps it up with a short walk leading to the ensemble’s finale.

Mike Berniker and Nat Shapiro produced Tubby The Tenor, and it’s unknown who the recording engineer is. However, this Classic Records reissue is an excellent recording with a superb soundstage. Bernie Grundman remastered this album, and it is an outstanding pressing using 180-gram audiophile vinyl that’s silent until the music starts. The front and rear covers also have a high gloss. Though known as a tenor saxophonist, Tubby Hayes played the flute and vibraphone equally proficiently. Until this album, I only knew of his work as a member of The Jazz Couriers with Ronnie Scott, but I am now on the hunt for more of his records. If you’re a fan of the tenor sax, I invite you to check out Tubby The Tenor by The Tubby Hayes Sextet on your next vinyl shopping trip. It’s an ideal introduction to this remarkable musician and an enjoyable album you can listen to any time of the day or evening!

~ Tubbs in N.Y. (Fontana TFL 5183/STFL 595) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Aireign – Source: JazzStandards.com ~ Columbia Studio A – Source: Tubby Hayes: How The Little Giant Conquered The Big Apple by Simon Spillett. Jazzwise Magazine, October 18, 2021. www.jazzwise.com ~ Doxy, Soon – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2023 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone