Requisites

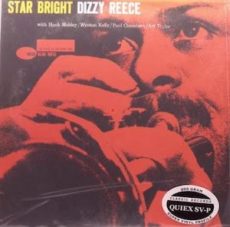

Star Bright ~ Dizzy Reece | By Eddie Carter 3.7.21

This morning’s choice from the library comes from a young man from Kingston, Jamaica. Alphonso Son Reece attended the Alpha Boys School where he began playing the baritone sax before switching to the trumpet at age fourteen. It’s also during this time where he got his nickname Dizzy, which had nothing to do with Dizzy Gillespie. He became a professional musician at sixteen and has played with some of the greatest jazz musicians in England, France, and the United States. Star Bright (Blue Note BLP 4023/BST 84023) was released in 1959 and is his third album as a leader following Progress Report (1957), and Blues In Trinity (1958). He’s backed on this date by three musicians he only knew from their records, Hank Mobley on tenor sax, Wynton Kelly on piano, and Paul Chambers on bass. Completing the quintet is Art Taylor on drums who played with Dizzy on Blues In Trinity. My copy used in this report is the 2003 Classic Records Mono audiophile reissue (BLP 4023 – BN 4023).

Side One starts at a relaxed tempo with The Rake, one of four tunes Reece composed for the 1958 British film, Nowhere To Go. The quintet opens with a laid-back stroll through the melody, and Dizzy lays down an easy-going opening solo. Hank follows with a reading so comfortable and cozy, you almost feel his warm personality coming from your speakers. Wynton glides into the closing statement gracefully with Paul and Art backing him leading to the reprise.

The pace picks up for the 1945 tune, I’ll Close My Eyes by Billy Reid and Buddy Kaye. Reid originally wrote this song as one of regret and remorse, but Kaye updated the lyrics, making the song upbeat. The trio creates the down-home atmosphere for the leader’s perfectly crafted opening chorus. Mobley begins with a stirring performance, followed by a spirited statement by Reece. Kelly achieves a wonderful groove on the next reading and Chambers walks with passionate precision on the climax.

The quintet takes a trip to Groovesville next, an impromptu blues by Dizzy beginning with the first of two statements by Wynton. The pianist opens this happy swinger with a blues-rooted energy that’s highly contagious. Dizzy takes charge next with a cheerfully buoyant interpretation, then Hank expresses his excitement on the third reading. Wynton picks up where he left off with a second clever statement preceding the front line splitting the closing chorus and the coda.

Side Two gets underway with Dizzy’s The Rebound, a medium-fast original that commences with the ensemble stating the melody collectively. Reece kicks things off with a feisty first reading, then Mobley takes the next spot, his tenor sax soaring with a soulful charm. Kelly answers enthusiastically with a high-spirited interpretation, and Chambers makes the final solo sparkle with a concise contribution before the ensemble takes the song out.

I Wished On The Moon was written in 1935 by Dorothy Parker and Ralph Rainger. It would become a big hit for Bing Crosby who recorded it that year with The Dorsey Brothers Orchestra. The group’s approach to this familiar evergreen is laid-back with Dizzy leading the trio through the carefree theme and finale with inspired interpretations by Dizzy, Hank, and Wynton who make it look so easy. Dizzy’s A Variation on Monk sets off at a brisk uptempo pace by Kelly, and the rhythm section evolves into a vigorous collective opening chorus. Mobley charges into the lead solo with an invigorating performance, then comes Reece who’s firing on all cylinders with an exhilarating statement. Kelly matches the front line’s intensity with a marvelous presentation that’s over too quickly. Taylor begins his only solo opportunity with an exchange of ideas between himself and both horns, then gives the final statement some vigorous brushwork ahead of the closing chorus.

A lot of thought and care went into the remastering of Rudy Van Gelder’s original tapes by Bernie Grundman of Bernie Grundman Mastering. The music is superbly recorded with a breathtaking soundstage and the instruments emerging from your speakers as if the musicians are playing right in front of you. The record was pressed on 200–gram Quiex SV–P Audiophile Vinyl with a flat–edge and deep groove on the label. It’s silent until the music begins. If you’re a fan of Hard-Bop from that magic year of 1959 and aren’t familiar with Dizzy Reece, I offer for your consideration, Star Bright, a stellar album that’s one of the brightest stars in his discography and one I can happily recommend for your library!

~ Blues In Trinity (BLP 4006/BST 84006), I Wished on The Moon (Decca 39857), Progress Report (Tempo Records TAP 9) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Alphonso Son Reece, I’ll Close My Eyes, I Wished on The Moon – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2021 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,trumpet

Requisites

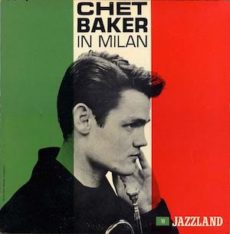

Chet Baker In Milan ~ Chet Baker | By Eddie Carter

The year 1959 was very good for jazz, several albums recorded and released that year would become contemporary classics and a significant few, acknowledged masterpieces. It was also a good year for Chet Baker, three LP’s he recorded are considered among his best, Chet, Chet Baker Plays The Best of Lerner & Lowe, and this morning’s choice from the library, Chet Baker In Milan (Jazzland JLP-18/JLP 918S). On this date, the trumpet player made during an extended tour through Germany and France, Chet’s working with five promising Italian musicians, Glauco Masetti on alto sax, Gianno Basso on tenor sax (tracks: A1 to A4, B1, B2), Renato Sellani on piano, Franco Cerri (listed as Serri) on bass, and Gene Victory on drums. My copy used in this report is the 1989 Original Jazz Classics Mono reissue (Jazzland OJC-370).

The opener, Lady Bird was written in 1939 by Tadd Dameron, and the sextet starts with a feisty theme statement. Chet opens with a vibrantly energetic reading set to an almost danceable beat, then Gianno follows with an enthusiastic improvisation. Glauco accentuates the bluesy momentum with a very enjoyable statement. Renato shows off his startling speed on the closer before the front line gives a few final verses.

Cheryl Blues by Charlie Parker was composed in 1947 and originally titled Cheryl. The sextet introduces the relaxing melody collectively. Baker is up first and makes the lead statement extremely interesting, then Basso gives the next spot a meaty interpretation. Masetti is as cool as a fresh breeze on a hot day next, and Sellani executes a fine touch and a steady hand to the finale.

The ensemble moves back into uptempo territory on Tune-Up by Miles Davis. It was written in 1953 and made its debut on the album, Miles Davis Quartet (1954). The sextet begins the melody with a swift-paced delivery, then Chet takes off first with astounding energy. Glauco follows with a feisty attack, and Gianno swings fiercely on the third solo. Renato provides a sparkling climax ahead of the front line’s final exchange into the ending.

Line For Lyons by Sonny Rollins begins with the unison theme at a medium tempo. Baker makes the first move with a cool tone, and Basso gives the second reading a pleasing rhythm. Masetti expresses himself fluently on the next interpretation. Sellani turns in a very attractive presentation next and Serri takes his first solo opportunity with a noteworthy closing statement.

Pent-Up House by Sonny Rollins starts Side Two and was first heard on the album, Sonny Rollins Plus 4 (1956). The sextet begins the opening chorus jointly. Chet sets the groove with a spirited statement, then Gianno solos confidently next. Glauco follows with a bristling interpretation. Renato provides a short, pithy presentation, then the front line shares a brief exchange leading to a soft climax.

The ensemble takes a page from The Great American Songbook for the 1919 song, Look For The Silver Lining by Jerome Kern and Buddy DeSylva. This tune was featured in two musicals, Zip, Goes A Million, that year, and Sally, a year later. The ensemble opens this oldie, but goodie with a finger-snapping mid-tempo theme. Baker, Masetti, Basso, and Sellani deliver four lively statements ahead of the reprise.

The 1919 song, Indian Summer was written by Victor Herbert who composed it originally as an instrumental piano piece. It became a jazz standard in 1939 after Al Dubin added the lyrics. For this song, Baker’s trumpet is marvelously lyrical with an amorous romantic beauty in his sound. This is particularly noticeable in the opening statement by Baker and a closing performance by Sellani that’s lavishly flavored with exceptional phrasing.

The album wraps up with the 1934 ballad, My Old Flame by Sam Coslow and Arthur Johnston. It opens with a gorgeous introduction and tender melody by Baker who almost seems to identify with the love, loss, and heartbreak of the lyrics in his opening statement and closing chorus. Sellani also gives a memorable account that’s brief, but beautifully nuanced and matched by Serri and Victory who support both soloists in perfect harmony.

Alto saxophonist Glauco Masetti was classically trained on violin and attended the Milan and Turin conservatories. He was self-taught on reed instruments and worked often as a session musician from the forties to the sixties. He also worked with Gianni Basso, Gil Cuppini, Giorgio Gaslini, Oscar Valdambrini, and Eraldo Volonté among others. Tenor man Gianni Basso was a renowned Italian saxophonist whose influence was Stan Getz. His career began after World War II as a clarinetist, before switching to the saxophone in The Belgian Raoul Falsan’s Big Band. Pianist Renato Sellani was also a composer who began his career as a professional in 1954 as a member of The Gianni Basso-Oscar Valdambrini Quintet. In 1958, he began a lengthy collaboration with his friend, guitarist, and bassist, Franco Cerri who turned ninety-five this past January. He was also a member of The RAI National Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Gorni Kramer, Kramer was also a noted musician and songwriter. He’s also worked with Bill Coleman and Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Enrico Rava, and Tony Scott.

Double bassist Franco Cerri is considered one of Europe’s most important musicians and learned to play guitar when he was seventeen years old. His influences were guitarists Barney Kessel, René Thomas, and Django Reinhardt. In 1945, he became a member of the group led by Gorni Kramer and joined the orchestra of the television show, Buone Vacanze (Happy Holidays). He started playing the double bass in addition to guitar in the fifties and has played with Lou Bennett, Buddy Collette, Stéphane Grappelli, Johnny Griffin, Lars Gullin, Billie Holiday, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Django Reinhardt, Tony Scott, Bud Shank, and The Modern Jazz Quintet. Giulio Libano who wrote the arrangements for the sextet was also an orchestra leader, jazz pianist, and trumpet player. He composed two songs that are featured in the 1961 Italian films, Girl With a Suitcase and Io Bacio…Tu Baci (Io Bacio…You Kiss)! Sadly, the only person I was unable to find any information on is drummer Gene Victory.

The description on the back cover giving the date of the entire recording as October 1959 is in error. Lady Bird was recorded on September 25, Cheryl Blues, Tune-Up, and Line For Lyons on September 26. Pent-Up House, Look For The Silver Lining, Indian Summer, and My Old Flame on October 6. I can’t provide the name of the engineer who originally recorded the album, but I can say with certainty it’s a superb recording that received excellent remastering by Phil De Lancie of Fantasy Studios. Baker is in excellent form throughout, the ensemble is watertight, and the level of soloing extremely high. If you’re a fan of Chet Baker and Cool Jazz, I highly recommend this album for a spot in your library. If you’ve read this far and are still uncertain, I’ll leave you with the first line of this report. The year 1959 was very good for jazz, Chet Baker In Milan, is one of the reasons why!

~ Chet (Riverside RLP 12-299/RLP-1135), Chet Baker Plays The Best of Lerner & Lowe (Riverside RLP 12-307/RLP 1152), Miles Davis Quartet (Prestige PRLP-161), Sonny Rollins Plus 4 (Prestige PRLP-7038/PRST-7291) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Girl With a Suitcase and Io Bacio…Tu Baci (Io Bacio…You Kiss) – Source: IMDB.com ~ Look For The Silver Lining, Indian Summer, Glauco Masetti, Gianni Basso, Renato Sellani, Franco Cerri, Giulio Libano – Source: Wikipedia.org ~ Lady Bird – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vwio99V8-cw ~ Cheryl Blues – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfbUraDG-mU © 2021 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,trumpet

Requisites

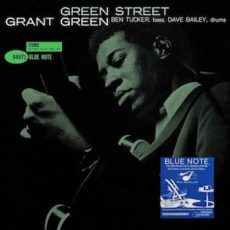

Green Street ~ Grant Green | By Eddie Carter

Grant Green steps into the spotlight with the second of four albums he released in 1961. Grant was one of the most interesting guitarists in jazz, possessing a gorgeous tone, speed of execution, and a distinctive lyricism in his playing that proved remarkably durable. He never failed to please his critics, fans, and peers throughout his career, but his time at Blue Note was particularly successful. Green Street (Blue Note BLP 4071/BST 84071) is a trio album like his label debut, Grant’s First Stand.

However, here the guitarist takes a different path than the usual organ/guitar/drums trio or a larger group featuring horns, a piano, or vibes to augment the rhythm section on later albums. His colleagues are Ben Tucker on bass, and Dave Bailey on drums. Both men provide a perfect backdrop for Grant to communicate a swinging style of jazz to the listener with rhythmic precision and finesse throughout the five-song set. My copy used in this report is the 2015 Music Matters Stereo audiophile reissue (MMBST-84071).

The first stop, No. 1 Green Street is a mid-tempo blues by the leader beginning with the trio presenting the catchy melody in unison. Grant takes over for the song’s only solo, giving him ample space to build an engaging statement that’s an ear pleaser with Ben and Dave pacing themselves behind him. ‘Round About Midnight by Bernie Hanighen, Thelonious Monk, Cootie Williams opens with a delicately tender theme by the trio continuing with an elegantly graceful showcase by the guitarist preceding a touching ending.

Green’s composition, Grant’s Dimensions ends Side One with high-spirited energy allowing Ben and Dave their first solo opportunity. Grant crafts a marvelous improvisation driving the rhythm firmly. Ben turns in a fine performance next with a bouncy bass interpretation flowing steadily into Dave’s impressive exchange with Green and Tucker ahead of the out-chorus.

Green With Envy by Grant begins Side Two affording each member a chance to speak individually with the leader giving the longest talk. After a vivacious melody by the trio, Grant delivers one of his most creative interpretations with a satisfying summation. Ben is up next, carefully selecting and bending his notes into an excellent reading with feeling. Bailey participates in an aggressive exchange with Green and Tucker for the final performance possessing a youthful intensity before a superb end theme.

Alone Together by Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz was written in 1932 and featured in the Broadway musical, Flying Colors. The trio’s rendition lowers the temperature by a few degrees, opening with a subdued introduction and theme evolving into a virtuoso lead solo by Grant punctuated by the inspired foundation from Ben and Dave. The bassist provides a walking bass line on the final reading that’s clearly expressed and well-defined, swinging smoothly into the theme’s return and slow fade.

Anyone who’s heard or owns a Music Matters Jazz reissue knows of the attention to the music through their remastering of the original tapes by Rudy Van Gelder. The amazing gatefold photos, and the covers themselves are worthy enough to be considered as album art plus the meticulous pressing by RTI. I listened to Green Street after hearing my 1995 Blue Note Connoisseur Series Stereo reissue, using it for comparison since both are 180-gram audiophile reissues. I was impressed by the Connoisseur LP’s sound and the detail of the instruments is clearly defined. In my opinion, it’s one of the best-remastered albums I’ve ever heard from that series by Capitol Records. However, when the stylus dropped on the MMJ 33 1/3 reissue, I discovered an extraordinary soundstage across the treble, midrange, and bass spectrum that’s absolutely mind-blowing.

There’s only one error on the LP, it appears on the Side Two label. Track Two is incorrectly listed as the 1937 song, Where Are You? by Jimmy McHugh and Harold Adamson. That tiny issue aside, if you’re a fan of jazz guitar by Kenny Burrell, Pat Martino, Wes Montgomery, Jimmy Raney, and Joe Pass, I enthusiastically invite you to take a trip to Green Street on your next record hunt. There you will find a jazz album that’s a real pleasure to listen to and sounds just as fresh today as when first released by one of the elite guitarists of Hard-Bop, Grant Green at the peak of his creativity! ~ Grant’s First Stand (Blue Note BLP 4064/BST 84064); Green Street (Blue Note Connoisseur B1-32088) – Source: Discogs.com ~ ‘Round About Midnight, Alone Together – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,guitar,history,instrumental,jazz,music

Requisites

Flute Fever ~ The Jeremy Steig Quartet | By Eddie Carter

The word impossible as defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary is “something that’s incapable of being or of occurring”. In the annals of music, some amazing musicians and vocalists have met the challenge of their disabilities head-on and in doing so, changed the word impossible to I’m possible instead! Jeremy Steig was an artist, graphic designer, and musician who began playing the flute at twelve and jazz at fifteen. At age nineteen, a motorcycle accident paralyzed one side of his face that might have ended his music career. It didn’t, because he used the paralysis within his mouth to blow air into the flute with the help of a special blinder-like mouthpiece that was placed inside his cheek, allowing him to play.

This morning’s album from my library is titled Flute Fever (Columbia CL 2136/CS 8936) by The Jeremy Steig Quartet. The other members are Denny Zeitlin on piano, Ben Tucker on bass, and Ben Riley on drums. An example of Jeremy’s artistic talent appears on the front cover. He also penned four drawings of the group on the back cover, and my copy used in this report is the 1964 Stereo LP.

Side One opens with Oleo by Sonny Rollins, he wrote it in 1954 and premiered it on the album, Miles Davis With Sonny Rollins. Jeremy and Tucker start the song as a duet with a strong rhythmic beat that takes off by leaps and bounds when Denny and Riley come in for the collective theme. Jeremy infuses the opening reading with zestful virtuosity as he vocalizes along on a vigorously swinging interpretation. Denny revs up the short and sweet closing statement with a soaring, exhilarating lyricism ahead of the leader’s ending theme and abrupt climax.

Lover Man (Oh, Where Can You Be?) by Jimmy Davis, Roger Ramirez, and Jimmy Sherman was composed in 1941 for singer-songwriter Billie Holiday. The quartet’s rendition opens with Steig leading a delicately gentle melody. Zeitlin gives a very touching performance on the song’s only solo preceding the foursome’s haunting tenderness on the coda. Sadly, omitted from this version are two elegant performances by Steig and Tucker, and a well-deserved compliment from the engineer at the song’s end that appears on the CD-album.

What Is This Thing Called Love?The Cole Porter song from the 1930 Broadway musical, Wake Up and Dream takes the foursome back to uptempo. After an effervescent melody, Jeremy begins with an exhilarating reading. Denny answers the flutist with an electrifying solo that excites intensely until the foursome’s coda. Miles Davis’ So What begins with Steig wailing on the opening, then continuing with a lengthy adrenaline rush of energy on the first interpretation. Zeitlin takes the next reading for a sizzling rollercoaster ride, then Tucker briskly walks on the closer.

The quartet takes on Thelonious Monk’sWell You Needn’t to begin Side Two. Monk wrote the tune in 1944 and was going to name it after jazz vocalist, Charlie Beamon, who upon hearing that replied, “Well, you need not”. The song starts at medium-fast speed for the quartet’s collective opening chorus. Jeremy steps into the spotlight first, igniting his solo with the brightness of an incandescent sun. Denny begins the final statement with no accompaniment for one chorus, before settling into a dazzling performance that’s a bebopper’s dream.

The beautiful 1932 song Willow Weep For Me by Ann Ronell is enchantingly rendered collectively with Jeremy’s flute conversing her lyrics daintily over a politely subdued supplement from the rhythm section. Denny contributes a brief interlude that’s beautifully constructed in between the opening and ending melodies by Jeremy culminating with a heart-warming finale. The LP ends with the album’s longest tune, Blue Seven by Sonny Rollins. The guys have fun right out of the gate with Steig and Tucker starting an easy-flowing duet that develops into a bluesy mid tempo opening chorus when Zeitlin and Riley join them. Jeremy and Denny have the two lengthiest statements and both men provide two meticulous but playful performances that take no prisoners. Tucker lays down some new soil on the next reading with a laid-back lyricism shadowed closely by Riley who doesn’t solo but contributes some bouncy brushwork that’s infectiously light-hearted and complements the soloists very well.

Jeremy Steig is the son of cartoonist William Steig whose work appeared in the weekly magazine, The New Yorker. His father also created the character Shrek, and Jeremy played the role of The Pied Piper on flute for the film, Shrek Forever After (2010). His mother, Elizabeth Mead Steig is the head of the fine arts department at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He recorded with pianist Bill Evans on the album, What’s New (1969), a critical success for both musicians. Steig became even more successful in the jazz-rock fusion genre in the seventies, recording a total of twenty-two albums during his career. Jeremy lived with his wife Asako in Japan and passed away from cancer at age seventy-three on April 13, 2016.

Pianist Denny Zeitlin, the lone survivor of the quartet, impressed producer John Hammond so much with his performance on Flute Fever, he also produced his debut album, Cathexis (1964). He recorded three more LP’s over the next three years, Carnival (1964), Shining Hour – Live at The Trident (1966), and Zeitgeist (1967). Denny recorded thirty-five albums over his five-decade career playing with some of the greatest names in jazz. He’s currently a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California in San Francisco, and also has a private practice there and in Marin County.

Bassist Ben Tucker has a very lengthy resume of the albums he appeared on and the musicians he played with. Ben worked with The Dave Bailey Quintet in 1961 and composed the song Comin’ Home Baby. It became a hit for Bailey on 2 Feet In The Gutter that year, and flutist Herbie Mann on Herbie Mann at The Village Gate (1962). Tucker owned two stations in his hometown of Savannah, Georgia, WSOK-AM and WLVH-FM. He passed away at age eighty-two in a traffic collision on June 4, 2013.

It might be easier to tell you who Ben Riley didn’t play with because his list of recordings is also enormous. He’s most known as the drummer in The Thelonious Monk Quartet. He was also a member of The New York Quartet and in the group Sphere. He passed away on November 18, 2017, at the age of eighty-four.

The album was produced by John Hammond but does not offer any other information on the recording engineer. However, the sound quality is absolutely sensational with a superb soundstage that’s startingly clear from your speakers to your sweet spot. If you’re a fan of jazz flute, I submit for your consideration on your next vinyl hunt, Flute Fever by The Jeremy Steig Quartet. It’s one illness, you won’t mind catching and requires only one listen to make you feel much better!

~ Carnival (Columbia CL 2340/CS 9140); Cathexis (Columbia CL 2182/CS 8982); Herbie Mann at The Village Gate (Atlantic 1380/SD 1380); Miles Davis With Sonny Rollins (Prestige PRLP 187); Shining Hour – Live at The Trident (Columbia CL 2463/CS 9263); 2 Feet In The Gutter (Epic LA 16021/BA 17021); What’s New (Verve Records V6-8777); Zeitgeist (Columbia CL 2748/CS 9548) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Oleo, Well You Needn’t, What Is This Thing Called Love? – Source: JazzStandards.com

~ John Hammond, Ben Riley, Ann Ronell, Jeremy Steig, William Steig, Elizabeth Mead Steig, Ben Tucker, Denny Zeitlin – Source: Wikipedia.org

~ Oleo – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1bX-9Q6Qsc ~ So What – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jsBruIp_qnI © 2021 by Edward Thomas CarterMore Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,flute,history,instrumental,jazz,music

Requisites

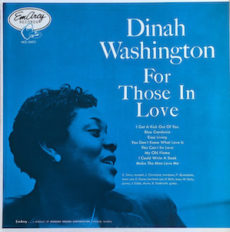

For Those In Love ~ Dinah Washington | By Eddie Carter

To the singer of jazz ballads, standards, or contemporary hits, a song is comprised of three essential parts, melody, harmony, and rhythm. When all three elements are mixed, and enhanced by great arrangements and musicians, the result is an enriching music experience. This morning’s choice from the library is by Dinah Washington, a vocalist who sang the blues, jazz, pop, and R&B proficiently. The album is For Those In Love (EmArcy MG 36011), recorded and released in 1955. She’s joined on this date by Clark Terry on trumpet, Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, Paul Quinichette on tenor sax, Cecil Payne on baritone sax, Wynton Kelly on piano, Barry Galbraith on guitar, Keter Betts on bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums. The arrangements are by Quincy Jones and my copy used in this report is the second 1955 US Mono release featuring the silver Mercury Records oval at the noon position of the label with EmArcy Jazz appearing in the bottom of the oval.

The opener is I Get a Kick Out of You, written by Cole Porter for the 1934 Broadway musical, Anything Goes, and the octet gets right to work on this swinger. Dinah has the spotlight first and gives a splendidly entertaining improvisation. Jimmy follows, having a ball on a spirited statement, then Kelly displays impeccable chops on a relaxed reading. Clark comes in for some savory swinging with a mute on the closing solo, and Dinah handles the finale with great effectiveness leading the group into a slow fade. Blue Gardenia by Lester Lee and Bob Russell was composed for the 1953 crime drama, The Blue Gardenia. It became a signature song for Dinah and the octet offers a supporting role behind her delicately subtle narrative. Quinichette gives a brief statement of tenderness, then Galbraith offers a solo of soft tranquility. Payne has a moment in the spotlight adding a dreamlike softness to the closing solo. Dinah wraps up the song with emotional sensitivity on the climax.

Easy Living by Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin was the main theme of the 1937 comedy of the same name. The group provides a perfect complement to Dinah’s luxurious vocals on the opening chorus, and the solo order is Paul, Clark, and Jimmy. The first two readings are like delicate porcelain figurines, perfectly proportioned and translucent. The pace picks up slightly for the trombonist who plays the next interpretation with sensual beauty. Ms. Washington is especially attractive on the reprise with a velvety, smooth timbre in her voice that’s gorgeous. You Don’t Know What Love Is by Gene de Paul and Don Raye is a perfect song for film-noir. The haunting lyrics describe the hurt and sadness at the end of a love affair. It opens with a solemn introduction by Dinah and Galbraith. She captures the subtle pathos of the song with the octet’s soft supplement. Cleveland provides the song’s only solo with a graceful and elegant interpretation before Dinah returns to the melancholy mood of the beginning.

This Can’t Be Love by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart was written in 1938 and featured in the Broadway musical, The Boys From Syracuse. The mood is jubilant, and Dinah rises to the occasion with a vivacious vocal treatment. Clark’s muted trumpet sets a lively mood on the first solo. Cecil is up next with an energetic performance of his own. Jimmy mines a vein of unsuspected riches on the third statement, then Paul delivers a delightful interpretation. Kelly cooks up a mesmerizing musical brew before Dinah sings the closing chorus. My Old Flame by Arthur Johnston and Sam Coslow made its debut in the 1934 film, Belle of The Nineties. Dinah begins this tune as a duet with Galbraith preceding the rhythm section’s slow-tempo theme. She’s the dominant presence here and presides with authority, as she recounts her lost love some time ago in a reflective flashback. The horns make their presence known for the closing chorus with Dinah giving it the recognition it deserves.

The 1940 show tune by Rodgers and Hart, I Could Write A Book gets taken for a mid~tempo spin by Ms. Washington and the ensemble. The octet starts the song in unison for the introduction, then Dinah treats the listener to an effervescent vocal performance on the melody. Paul starts with a passionately playful lead solo. Terry adds some fire on the muted trumpet, then Cleveland ends the solos on an upbeat note. The album’s finale, Make The Man Love Me is by Arthur Schwartz and Dorothy Fields. Quinichette opens with a seductive introduction, then Dinah makes a passionate romantic plea with the lyrics. Paul takes the lead with a remarkably graceful solo, then Terry turns in a beguilingly beautiful statement. Kelly approaches the next performance with affective empathy and Cleveland soothes the soul on the closer. Dinah sings two verses of the Duke Ellington–Paul Francis Webster classic, I Got It Bad (and That Ain’t Good) before returning to the original lyrics for the coda.

It’s a solid summation to an album sparkling with marvelous music, exciting, evocative solos, excellent arrangements, and the extraordinary vocals by Dinah Washington that are exceptionally presented. She brought the lyrics she sang to life in each song. The Queen of The Blues, a title she gave herself, recorded a total of thirty-three LP’s for EmArcy, Mercury, and Roulette during her short recording career that began in 1952 and lasted only eleven years. Though her greatest hit, What a Difference a Day Makes came four years later in 1959, For Those In Love would become one of the strongest albums of her career. Dinah passed away from a drug overdose on February 14, 1963, at the age of thirty-nine. This is a gorgeous recording with a splendid soundstage that’ll take your breath away each time you listen. I found For Those In Love to be thoroughly enjoyable and recommend it as a wonderful starting point for any fan interested in exploring the music of Dinah Washington. After one audition, I’m sure you will too! ~ What a Difference a Day Makes (Mercury MG 20479/SR-60158) – Source: Discogs.com

~ I Get a Kick Out of You, Easy Living, My Old Flame, I Could Write a Book, I Got It Bad (and That Ain’t Good) – Source: JazzStandards.com ~ Blue Gardenia, Dinah Washington, Make The Man Love Me – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2021 by Edward Thomas

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,vocal