Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Thomas S. McIntosh was born February 6, 1927 in Baltimore, Maryland and studied at the Peabody Conservatory. During his time in the Army band he played trombone, followed by a move to New York in 1956 where he played with Lee Morgan, Roland Kirk, James Moody, Art Farmer and Benny Golson. During this period he also graduated from Julliard.

By 1961 he was composing “The Day After” for trumpeter Howard McGhee and two years later for Dizzy Gillespie’s “Something Old, Something New” album. The following year his composition “Whose Child Are You?” was performed by the New York Jazz Sextet, of which he was a member.

Working with Thad Jones and Mel Lewis in the late Sixties, as a leader McIntosh recorded Manhattan Serenade and worked with earl Coleman, Jerome Richardson, Billy Taylor, Frank Foster, Eddie Williams, Gene Bertoncini, Bobby Thomas and Reggie Workman. He arrange for Bobby Timmons and Milt Jackson, working as a sideman with the later and also Oliver Nelson and Shirley Scott.

Tom gave up jazz and moved to Los Angeles and began a long and successful career composing for film and television writing music for such films as The Learning Tree, Soul Soldier, Shaft’s Big Score, Slither, A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But A Sandwich and John Handy. In 2008 he was honored by the National Endowment for the Arts as a Jazz Master. Trombonist and composer Tom McIntosh passed away in his sleep at age 84 on July 26, 2017.

More Posts: trombone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Don Goldie was born Donald Elliott Goldfield on February 5, 1930 in Newark, New Jersey. While still a young boy, Goldie had started learning the violin, the trumpet, and the piano, and he was good enough on the trumpet to earn a $1,000 scholarship to the New York Military Academy, later studying with the New York Philharmonic’s Nathan Prager.

After Army service he relocated to Miami, Florida in 1954 winning the Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scout Award. This was followed with a gig with Bobby Hackett in New York and subsequent engagements and recording work with Lester Lanin, Neal Hefti and Jackie Gleason.

Catching the attention of Jack Teagarden, he joined the band in 1959 and was a part of Teagarden’s first Roulette recording “At The Roundtable”. Over the next three years he distinguished himself as a soloist and sharing the vocals including a perfect impersonation of Louis Armstrong.

After leaving the group, Don led his own band for a time, but by the late ’60s was working with Jackie Gleason in Miami Beach, as well as playing jazz and pop gigs of his own. He cut albums for Chess Records’ Argo offshoot and the Verve label in the early ’60s, and in the 1970s reemerged with his own Jazz Forum label, for which he cut a string of eight LPs, each dedicated to the works of a single composer. He released his final LP, “Don Goldie’s Dangerous Jazz Band” on the Jazzology label in 1982.

With declining health, mostly associated with diabetes, he was forced into retirement and on November 25, 1995 trumpeter Don Goldie committed suicide.

More Posts: trumpet

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

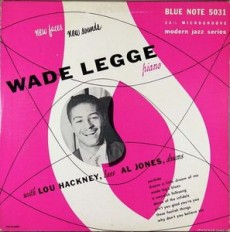

Wade Legge was born on February 4, 1934 in Huntington, West Virginia. He played more bass than piano in his early years, and it was with the bass that Milt Jackson first noticed him, recommending Wade to Dizzy Gillespie. After hiring him, Gillespie moved him to piano and he remained a member of Gillespie’s ensemble until 1954. During his Dizzy years, Legge recorded a date in France as a trio session leader.

Following his tenure with Gillespie, Wade moved to New York City and freelanced there, playing in Johnny Richards’s orchestra, and sessions with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Milt Jackson, Joe Roland, Bill Hardman, Pepper Adams, Jimmy Knepper and Jimmy Cleveland.

Legge was one of three pianists recording as a member of the variously staffed Gryce/Byrd Jazz Lab Quintets in 1957 and appeared on more than 50 recordings before retiring to Buffalo in 1959. Jazz bassist and pianist Wade Legge died on August 15, 1963 in Buffalo, New York at the age of 29.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

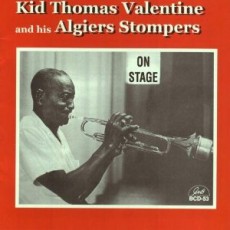

Kid Thomas was born Thomas Valentine on February 3, 1896 in Reserve, Louisiana and moved to New Orleans in his youth. Gaining a reputation as a hot trumpet man in the early 1920s, he started his own band in 1926, basing himself in the New Orleans suburb of Algiers.

Unaffected by the influence of Louis Armstrong and later developments of jazz, Kid Thomas had perhaps the city’s longest lasting old-style traditional jazz dance band, continuing to play in his distinctive hot, bluesy sometimes percussive style. Although Valentine played popular tunes of the day even into the rock and roll era, he played everything in a style of a New Orleans dance hall of the early 1920s.

Kid Thomas Valentine started attracting a wider following with his first recordings in the 1950s and played regularly at Preservation Hall from the 1960s through the 1980s. He toured extensively for the Hall, including a Russian tour, as a guest at European clubs and festivals, and working with various local bands as well as his own. During the 1960s Kid Thomas recorded extensively for the Jazz Crusade and GBH labels both with his own band and with Big Bill Bissonnette’s Easy Riders Jazz Band. He made over 20 tours with the Easy Riders in the U.S. Northeast.

By the mid 1980s, as Thomas’s strength started to wane, Preservation Hall management brought in Wendell Brunious, who took over much of his trumpet duties, though Kid continued to lead the band. On June 18, 1987, trumpeter Kid Thomas Valentine passed away.

More Posts: trumpet

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

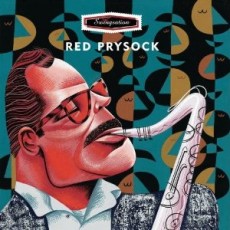

Red Prysock was born Wilburt Prysock on February 2, 1926 in Greensboro, North Carolina. One of the early Coleman Hawkins influenced saxophonists he played in both jazz and rhythm and blues worlds.

He first gained attention playing with Tiny Bradshaw’s band, playing the lead sax solo on his own composition “Soft”, which was a 1952 hit. He also played with Roy Milton and Cootie Williams. While with Tiny Grimes and his Rocking Highlanders, Prysock staged a memorable sax battle with Benny Golson on “Battle of the Mass”.

In 1954, he signed with Mercury Records as a bandleader and moving to R&B had his biggest instrumental hit, “Hand Clappin” in 1955. That same year, he joined the band that played at Alan Freed’s stage shows. He also played on several hit records by his brother and vocalist Arthur Prysock in the 1960s.

Red Prysock released five albums for Mercury and another two for Forum Circle and Gateway record labels. He passed away of a heart attack on July 19,1993 in Chicago, Illinois at the age of 67.

More Posts: saxophone