Requisites…

<Anthropology~Don Byas | By Eddie Carter

I begin this morning’s discussion with an album by tenor saxophonist Don Byas, a swing and bebop musician who played in the orchestras of Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Lionel Hampton. He also worked with Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Ethel Waters among others. Anthropology (Black Lion Records BLP 30126) is a 1963 album that was recorded live at the Jazzhus Montmartre (also known as Café Montmartre). The rhythm section is an outstanding trio of Danish descent, pianist Bent Axen, bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen and drummer William Schiöpffe. My copy used in this report is the US Stereo reissue (Black Lion BL-160), the date of release is unknown.

The album opens with Anthropology, a bebop classic written in 1945 by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker that’s also known as Thriving From a Riff or Thriving on a Riff. Schiöpffe introduces the tune, preceding the leader’s feisty delivery of the melody. Byas takes the lead with a compelling lift to start the soloing, then Axen executes the second reading efficiently. Pedersen turns in a brief presentation closely shadowed by Byas and Schiöpffe ends the readings by exchanging a few splendid phrases with the leader.

Moonlight In Vermont was written in 1944 by John Blackburn and Karl A. Suessdorf. This timeless evergreen provides a perfect backdrop for Byas’ gorgeous melody. The saxophonist continues with a very dreamy interpretation of the slow-paced, serene opening solo. Bent follows, displaying a graceful elegance on the next performance with discreet, perfectly tailored support by Niels-Henning and William. Byas’ closing chorus is lovingly rendered, completing the song with a tender finale that’s gorgeous.

Charlie Parker’s 1945 bebop anthem Billie’s Bounce ends the first side with a spirited rendition by the quartet. Pedersen and Schiöpffe open the song as a duet that becomes a lively theme treatment. Don raises the temperature on the lead solo with an effervescent beat that energizes the trio. Bent takes the spotlight last hitting a perfect groove on a swinging performance preceding the leader’s final remarks, theme’s reprise, and coda.

The gears shift upward for Dizzy Gillespie’s most famous recorded tune, Night In Tunisia was written in 1942 with Frank Paparelli. The rhythm section introduces the song at a speedy velocity proceeding to the aggressively energetic theme by Byas who also rips into the first solo voraciously. Bent takes the reins next zipping along like a whirlwind, then Don returns for a second exhilarating statement with bassist and drummer providing the fuel. NHØP takes over for an abbreviated scorcher, then Schiöpffe speaks last exhibiting mesmerizing brushwork into the invigorating climax.

The finale is the 1932 ballad, Don’t Blame Me, written by Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields. This song made its first appearance on Broadway in the show, Clowns in Clover, and later in two films, The Bad and The Beautiful (1952) and Two Weeks in Another Town (1962). Byas begins with a delicate introduction and heart-warming melody ahead of a sultry first statement that’s exquisite. Axen expresses a gentle affection on the final solo preceding Byas who ends the song and LP with a tender sincerity.

In 1964, Byas was celebrating his third decade as a professional musician. In honor of that achievement, the LP was also released as The Big Sound – Don Byas’ 30th Anniversary Album on Fontana in the Netherlands and Debut Records in Denmark. Two songs on the original LP are omitted on Anthropology, There’ll Never Be Another You by Harry Warren and Mack Gordon and Walkin’ by Richard Carpenter. Don Byas was a masterful musician who was adept at a fast clip or on a romantic ballad.

He lived the last twenty-six years of his life in Europe, working extensively before passing away from lung cancer on August 24, 1972, at the age of fifty-nine. The dialogue between the quartet is fascinating and their music a treat for the Café Montmartre crowd. The album was produced by UK music executive Alan Bates who began Black Lion Records and also re-launched the Candid label in London. The sound quality is excellent, transporting the listener to the club amid the crowd. Though out of print for many years, Anthropology is a remarkable live album by Don Byas that I not only recommend but am sure will become a welcome addition in any library.

~ Alan Bates, The Big Sound – Don Byas’ 30th Anniversary Album (Debut Records DEB-142, Fontana 688 605 ZL) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Moonlight In Vermont, Night In Tunisia – JazzStandards.com ~ Don’t Blame Me – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Requisites

Big Blues ~ Art Farmer & Jim Hall | By Eddie Carter

This next choice from the library I acquired after hearing a selection on SiriusXM’s Real Jazz channel. The album is titled Big Blues (CTI Records CTI 7083), released in 1979 and the two men co-leading this enjoyable date are Art Farmer on flugelhorn and Jim Hall on guitar. Rounding out the ensemble are Mike Mainieri on vibes, Mike Moore on bass, and Steve Gadd on drums. My copy used in this report is the 2017 ORG Music Stereo Audiophile reissue (ORGM-2019).

The song that initially sparked my interest leads off the first side, Benny Golson’s 1956 contemporary jazz classic, Whisper Not! It’s one of his most recorded compositions and also became a beloved vocal after Leonard Feather added lyrics in 1962. The quintet jointly creates a mellow melody with a blues beat to begin the song. Jim makes his guitar sing first with a relaxed casualness and steady rhythm. Art gets into an infectious laid-back groove next moving upward with bright chops and impeccable prowess. Mike takes over for the finale with an astonishing drive and intensity preceding the reprise and gentle coda.

The 1969 jazz standard, A Child Is Born by Thad Jones closes the first side starting gently with a brief introduction and tender theme by the rhythm section. Farmer starts the soloing with a ravishingly beautiful, muted performance, followed by Hall who delivers passionately elegant lines on the next interpretation. Mainieri gives a delicately gentle and evocative presentation recalling the spirit and imagination of the song’s composer into the serenely beautiful climax. Big Blues by Jim Hall starts the second side with a spirited midtempo opening chorus by the ensemble and the solo order is the same as on Whisper Not. Jim takes the lead here, showing us his versatility with charming articulation. Art follows, using the mute to deliver skillful assertion on the next reading. Mike’s closing statement is captivating from the moment it starts, expressing joy into the reprise and fadeout. Pavane For A Dead Princess by Maurice Ravel ends the album and was written as a solo piano piece in 1899. The song’s original title is Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a Dead Infanta) and the ensemble begins the introduction and melody at a slow tempo fitting the original composition. Farmer steps up first, back on the open horn, beginning as he did on the theme, then raises the temperature to midtempo before returning to a softer mood for the close. Mainieri pulls out all the stops on the next reading with a sparkling presentation. Hall takes the final bow with a gorgeous performance preceding the reprise and graceful fadeout.

Big Blues was originally produced by Creed Taylor and engineered by David Palmer who worked at Electric Lady Studios, and Joel Cohn who’s worked on many CTI albums. This reissue was mastered from the original analog tapes by Bernie Grundman and pressed on 180-gram Audiophile vinyl at Pallas Group in Germany. As was the case of many of the classic CTI Records, the sound quality is first-rate with an excellent soundstage across the highs, midrange, and low end that won’t disappoint the listener in their favorite spot to listen to music. Art Farmer and Jim Hall recorded together four other times, Interaction (1963), Live at The Half Note, To Sweden With Love (1964), and Panorama-Live at The Village Vanguard (1997). Each is highly recommended, and I feel the same can be said for Big Blues. I invite you to make time for this one on your next vinyl hunt, it’s an enjoyable album of Contemporary Jazz with extraordinary chemistry, and exceptional performances you won’t soon forget!

~ Interaction (Atlantic 1412/SD 1412); Live at The Half Note (Atlantic 1421/SD1421); Panorama-Live at The Village Vanguard (Telarc Jazz CD-83408); To Sweden With Love (Atlantic 1430/SD 1430) – Source: Discogs.com

~ Whisper Not, A Child Is Born ~ Source: JazzStandards.com

~ Pavane For A Dead Princess ~ Source: Wikipedia.org

© 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,guitar,history,instrumental,jazz,music,trumpet

Requisites

Yuko Mabuchi Trio, Volume 2 | By Eddie Carter

I’d reached the end of a very long day and was ready to relax and unwind with some piano jazz. I went to the library and came across Yuko Mabuchi Trio, Volume 2 (Yarlung Records YAR71621-161V). The second LP from the trio’s live performance at The Brain and Creativity Institute’s Cammilleri Hall with bandmates, Del Atkins on bass and Bobby Breton on drums. The concert honored the 25th Anniversary of The Los Angeles and Orange County Audio Society, plus President and CEO, Bob Levi’s 70th Birthday. My copy used in this report is the 2018 45-rpm Stereo Audiophile release.

Yuko starts Side One with a trio of solo standards, All The Things You Are by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, Take The “A” Train by Billy Strayhorn, and Satin Doll by Duke Ellington, Strayhorn, and Johnny Mercer. She begins with a stunningly beautiful interpretation capturing the song’s romanticism. Yuko then takes a vivaciously playful ride on The “A” Train with zestful excitement. She wraps up the trilogy with an invigorating interpretation of Satin Doll receiving an ovation from the audience at the song’s end.

The ensemble begins a Japanese Medley trilogy next, Hazy Moon by Teiichi Okano, Cherry Blossom, the Japanese folk tune from the Edo period, and Look At The Sky by Hachidai Nakamura. Yuko opens with a gentle introduction developing into a subtle collective theme. The mood of this first melody is incredibly tender, and the soothing splendor of her solo is purely captivating. She also dominates on the second segment, bringing out the musical substance and expressive beauty in an attractive reading culminating with a regal coda. The finale picks up the pace with the trio fitting together like fingers in a glove on the lively theme. Her technique is assured and quite confident in a dazzling exhibition against the backdrop set up perfectly by Del and Bobby.

Side Two starts with Sona’s Song, the pianist’s very touching tribute to a beautiful young girl in her family. The threesome makes the most of this original with seamless pacing and execution. Yuko demonstrates a mature elegance and heartfelt love in every note of her reverently lush performance before a serene summation. The group takes the audience and listener to the Caribbean on Sonny Rollins’ signature song, St. Thomas with a festive holiday atmosphere right from the start. Yuko invites everyone to enjoy the ride on a jubilantly cheerful lead statement with Atkins and Breton sustaining the rhythm. The drummer adds some buoyant brushwork for a propulsive reading before Yuko puts the finishing touches on a memorable, jazz-filled celebration.

Like its companion, Yuko Mabuchi Trio, Volume 2 has an outstanding soundstage across the highs, midrange, and low end, making it a good choice to show off a high-end audio system. This album was engineered by Bob Attiyeh and Arian Jansen, and mastered by Attiyeh, and Steve Hoffman. The 45-rpm remastering is by Bernie Grundman. The trio’s musicianship is excellent throughout the album and they shift gears as smoothly as a sports car. I’ll leave you with what I think is an ideal ending for my report, it comes from an old 1960 LP by The Joyce Collins Trio: Girl Here Plays Mean Piano. Yuko Mabuchi does this very well and if you’re discovering her for the first time, you’re in for a treat!

~ All The Things You Are, Satin Doll, Girl Here Plays Mean Piano (Jazzland JLP 24), Take The “A” Train – Source: Discogs.com

~ St. Thomas – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano

Requisites

Pure Getz ~ The Stan Getz Quartet | By Eddie Carter

I enjoy listening to jazz when I’m reading and one of my favorite musicians to hear is Stan Getz. He became a favorite of mine after hearing The Girl From Ipanema and Corcovado from the 1964 album, Getz/Gilberto. I also got to see him perform live as a member of the 1972 Newport Jazz Festival All-Stars at Music Hall on July 6, 1972, in New York City. This morning’s choice from the library is Pure Getz (Concord Jazz CJ-188) featuring his quartet at the time, Jim McNeely on piano; Marc Johnson on bass; Billy Hart (tracks: A3, B1, B2) and Victor Lewis (tracks: A1, A2, A4, B3) on drums. My copy used in this report is the 1982 US Stereo release.

The album opens with an uptempo tune by Jim McNeely, On The Up and Up. The ensemble starts with an invigorating melody, then Stan moves right into a sizzling lead statement. Jim swings hard on the next solo with a bouncy effervescence and spirited lyricism. Marc responds with an impressive presentation that appeals at every turn, and Victor keeps the rock-solid beat flowing into a quick climax.

The pace slows down for Blood Count by Billy Strayhorn, originally written as a three-part work for Duke Ellington titled Blue Cloud. It was Strayhorn’s final composition for Duke before succumbing to cancer on May 31, 1967. Ellington himself only performed the tune twice after Billy’s passing. First at a Carnegie Hall concert later that year in August and on his touching 1968 tribute album in memory of Strayhorn, And His Mother Called Him Bill. The quartet delivers an evocatively moving melody and Getz blows a passionately delicate performance culminating with a compassionate coda.

Very Early by Bill Evans is a pretty tune written early in the pianist’s career that was featured on his 1962 album, Moon Beams. The quartet presents this song at an easy, relaxing tempo with Billy Hart on drums. Marc opens with a tenderly expressive solo, then Jim turns in an enchanting interpretation next. Stan weaves a gentle spell of tenderness on the closing statement with a wonderful warmth and presence.

Sipping at Bell’s by Miles Davis begins with a three-instrument chat between Getz, Johnson, and Lewis. McNeely joins the discussion for the informal melody, then Johnson carves out a clever opening reading. Getz is formidable on the next presentation with a sharp, crisp attack. McNeely permits his fingers full sway on an effectively swift performance, and Lewis connects with a lightness of touch on a brief statement that’s exceptionally smooth.

Side Two starts with I Wish I Knew, written in 1945 by Harry Warren and Mack Gordon. This is a very enjoyable rendition taken at midtempo with the solo order, Getz, McNeely, and Johnson with Hart behind the drums. Stan swings into a soulful tenor solo sticking close to the melody. Jim comes next for a delightfully pleasant reading, then Marc makes an indelible impression on the finale with an inspired statement.

Come Rain or Come Shine by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer was written in 1946 for the Broadway musical, St. Louis Woman and is a jazz and pop favorite with numerous recordings since its inception. The trio opens with a gentle introduction evolving into an emotional communication on the melody. Getz’s sound is perfectly suited to this ballad as he demonstrates on the lead solo with a beautiful tone and thoughtful musicality. McNeely handles the next interpretation with meticulous care, and Johnson closes with a gorgeous bass solo ahead of the leader’s sensuous ending.

Tempus Fugit, aka Tempus Fugue-it, was written in 1949 by Bud Powell and is a play on words meaning “time flies”. The quartet takes off at a torrid tempo on the opening chorus, Jim swings at a ferocious pace on the scintillating first solo. Stan exemplifies boundless energy on the second reading with breakneck speed, then Marc gives the third reading a serious jolt of electrical energy. Victor wraps up the album with some bouncy brushwork before the quartet makes a spirited sprint to the finish line.

The album was recorded by Ed Trabanco and Phil Edwards, and the more I listened, the more I became impressed with the record’s soundstage. The instruments leap out of your speakers with outstanding detail. Stan Getz was one of the master tenor men with a career spanning nearly five decades from the forties to 1990. If you’re a fan of Bebop and Cool Jazz, I offer for your consideration, Pure Getz by The Stan Getz Quartet. An entertaining album that any jazz fan would appreciate!

~ And His Mother Called Him Bill (RCA LSP-3906); Getz/Gilberto (Verve Records V-8545/V6-8545); Moon Beams (Riverside RLP 428/RLP 9428) – Source: Discogs.com

~ Come Rain or Come Shine – Source: JazzStandards.com

~ Blood Count, Tempus Fugit – Source: Wikipedia.org

© 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Requisites

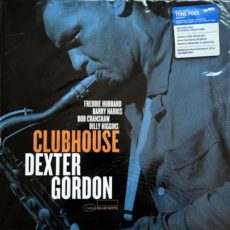

Clubhouse ~ Dexter Gordon | By Eddie CarterAny opportunity I get to discuss an album by tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon is always welcome, so I begin September with a recent addition to the library. Clubhouse (Blue Note Classic LT-989) is a date from 1965 that also produced the album, Gettin’ Around, but was shelved until 1979. The ensemble is a stellar one, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet; Barry Harris on piano; Bob Cranshaw on bass and Billy Higgins on drums. My copy used in this report is the 2019 Blue Note Tone Poet Series Stereo Audiophile reissue (Blue Note B0029356-01 – LT-989).

The quintet gets into some Hanky Panky to begin Side One with a melody march. Dexter swings with a bluesy beat on the opening statement. Freddie takes over for a neatly paced reading next. Barry ices the closer with a laid-back attitude into a marvelous finale. I’m A Fool To Want You is from 1951 by Frank Sinatra, Jack Wolf, and Joel Herron. Sinatra co-wrote the lyrics and recorded it for Columbia that year. Gordon expresses personal thoughts of lyrical reflection on the opening chorus and first solo. Hubbard and Harris also arouse tender emotions on two beautiful readings before the luxurious coda.

Devilette is by bassist Ben Tucker and was first heard on the 1971 live album, The Montmartre Collection, Vol. 1. This midtempo swinger makes a wonderful vehicle for the quintet to swing easily on the melody. Dexter struts smoothly into the first solo, then Freddie speaks proficiently next. Barry closes with an articulate, passionate interpretation ahead of the conclusion. The quintet convenes inside Gordon’s Clubhouse to start Side Two for a laid-back meeting offering everyone a solo opportunity. Harris gives a charming introduction blossoming into the ensemble’s collective theme. Gordon starts with a soulfully, mellow statement, then Hubbard offers some rhythmically incisive ideas. Harris follows for a melodic mix of grace and fire that’s especially effective. Bob has a definitive moment on the fourth interpretation and Billy wraps things up in a brief exchange with the front line. Jodi is a thoughtfully provocative tribute to Gordon’s wife at the time. Dexter opens with a perfect evocation of love on the melody and first solo. Freddie creates a concise mood of ecstasy next, and Barry adds a touch of sweet lyricism preceding the romantic ending.

The album ends with a tune by guitarist Rudy Stevenson that I first heard on the 1961 album Two Feet In The Gutter, Lady Iris B. The solo order is Gordon, Hubbard, Harris, Cranshaw, and their messages are full of joy and happiness into an immensely satisfying ending that’s positive and upbeat. Clubhouse was produced by Joe Harley of Music Matters Jazz and mastered by Kevin Gray of Cohearent Audio from Rudy Van Gelder’s original analog master tape utilizing 180-gram audiophile vinyl.

The Blue Note Tone Poet Series reissues include high-definition gatefold photos that are worthy of wall art and superb packaging of the covers. The music is simply amazing, and the sound is reference quality with a breathtaking soundstage that’s thrilling, to say the least. Dexter Gordon was a jazz master in every sense as a bandleader, composer, and tenor saxophonist. Clubhouse is nearly forty-minutes of exceptional jazz and an excellent choice for Blue Note to rescue from oblivion for any fan who loves Hard-Bop that you shouldn’t miss on your next vinyl hunt!

~ Gettin’ Around (Blue Note BLP 4204/BST 84204); I’m A Fool To Want You (Columbia 39425); The Montmartre Collection, Vol. 1 (Black Lion BL-108); Two Feet In The Gutter (Epic LA 16021/BA 17021) – Source: Discogs.com

~ I’m A Fool To Want You – Source: Wikipedia.org

© 2020 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone