Requisites

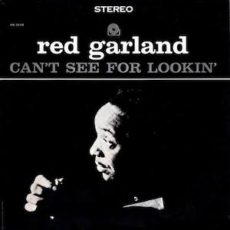

Can’t See For Lookin’ ~ Red Garland | By Eddie Carter

I was in the mood for some nice soothing music to enjoy after dinner a few nights ago when I came across this morning’s choice from the library by Red Garland. Can’t See For Lookin’ (Prestige PRLP 7276/PRST 7276) is his twelfth album and was recorded in 1958 but not released until 1963. William “Red” Garland was born in Dallas, Texas, and began playing the clarinet and alto sax before taking up the piano. He became famous in The Miles Davis Quintet from 1955 to 1958 and was well versed in the styles of Bebop, Hard-Bop, and straight-ahead jazz. After leaving Miles, he formed a trio and has recorded albums with Arnett Cobb, John Coltrane, Curtis Fuller, Jackie McLean, Charlie Parker, Art Pepper, Sonny Rollins, and Phil Woods. Here, he’s joined by Paul Chambers on bass and Art Taylor on drums. My copy used in this report is the 1972 US Stereo reissue (Prestige PRT-7276) by Fantasy Records.

Side One starts with a pretty song from the forties, I Can’t See For Lookin’ by Nadine Robinson and Dock Stanford. The trio begins an enchanting collective melody then Red glides into the first solo with a gracious amount of warmth and elegant simplicity. Paul walks through the second statement with a dreamy, rich tone revealing some intimate thoughts ahead of the trio’s delightful ending. Soon by George and Ira Gershwin began as a show tune from the musical, Strike Up The Band (1927). The ensemble gets things underway with a lively theme that’s passionate, enthusiastic, and extremely confident. Garland gives a stunning account on the opening solo with an energy that tweaks some new insights out of this old warhorse. Chambers makes his mark on the second reading with a showcase of incisively nostalgic ideas, and Taylor becomes a friendly sparring partner to the pianist on the closing statement.

Side Two opens with Blackout, a tune from the pen of Avery Parrish and Sammy Lowe beginning with an easy, caressing style by the ensemble on the melody. Red steps up first, establishing a nice momentum with a gorgeous opening statement. Paul approaches the next interpretation with great sensitivity and delicacy. Red returns to share a polite conversation with Art on the closing reading into a tender exit. Castle Rock by Al Sears brings the trio back to a brisk beat on the melody in unison. Garland leads off the opening statement with a light and nimble performance, then Chambers cooks up a tasty treat of cool jazz on the second solo. Taylor enters the spotlight last with Garland in a brief exchange into the closing chorus and happy ending.

Can’t See For Lookin’ was supervised by Prestige founder Bob Weinstock and Rudy Van Gelder was the man behind the dials. Both men are at the top of their game with a tremendous soundstage and incredible definition of each instrument. The piano has an amazing sound, and the bass and drums are perfectly balanced as if we’re in the studio while the musicians are recording. Red Garland recorded forty-six albums as a leader and was always good regardless of the setting or bandmates he appeared with. His career lasted over forty years and he continued recording until he suffered a heart attack, passing away on April 23, 1984, at age sixty. If you’re a Hard-Bop fan, enjoy Red Garland or jazz piano, I submit for your consideration, Can’t See For Lookin’. It’s thirty-five minutes of great music that you can file under “T” for terrific and perfect to enjoy while relaxing!

~ Soon – Source: Wikipedia.org © 2021 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: <!-- wp:paragraph --> <p><strong>choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano

Requisites

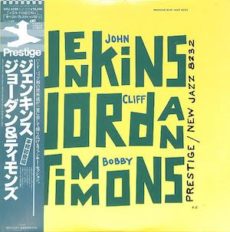

John Jenkins, Cliff Jordan, Bobby Timmons | By Eddie Carter

I begin this morning’s discussion with the 1960 collaborative album, Jenkins, Jordan, and Timmons (New Jazz NJLP 8232) by John Jenkins, Clifford Jordan, and Bobby Timmons. Joining them on this date are Wilbur Ware on bass and Dannie Richmond on drums. My copy used in this report is the 1981 Japanese Mono reissue by Victor Musical Industries (New Jazz SMJ-6299). John Jenkins’ approach to Hard-Bop and standards on the alto sax was distinctively tasteful. His solos always showed respect and affection for the tunes he played, and he could bring imaginatively unique lines even to well-worn standards. His other album as a leader is the self-titled release, John Jenkins (1957). Clifford Jordan’s interpretations on the tenor sax were the perfect characterization of his sound, sometimes growling, sometimes purring, but always with a formidable technique and a passionately assertive tone. Here, Jordan is in great form with another horn to joust with.

Pianist Bobby Timmons was one of the most talented yet neglected figures in the annals of Jazz. He composed two songs that are etched in the minds of many Jazz fans, Dat Dere, a mainstay in the early days of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet and Moanin’ that became a huge hit for The Jazz Messengers. Timmons appeared on the landmark album, Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers (1958). On this date, he approaches each tune with a melodic and rhapsodic touch that’s irresistible. Wilbur Ware was an extraordinary soloist on the bowed bass; he possessed a beautiful sound that could be fat, resonant, and fluid without any loss of body on any of the songs he played. Dannie Richmond is best known for his many albums with Charles Mingus, he’s a very pleasant surprise on this record with an energetic liveliness in his playing. He also recorded with many jazz greats including George Adams, Pepper Adams, Chet Baker, Ted Curson, Booker Ervin, Duke Jordan, Herbie Nichols, Horace Parlan, and Don Pullen.

Clifford Jordan’s Cliff’s Edge starts Side One at midtempo with both saxes flexing their muscles in unison on the opening chorus. Cliff is up first with a very satisfying opening solo at an easy, unhurried pace. John continues the conversation with a pleasant zest on the second performance. Bobby tells his story last with a charming interpretation that comes across effectively anchored by Wilbur and Dannie’s support into the quintet’s ending. Up next is the 1946 jazz standard Tenderly by Walter Gross and Jack Lawrence. Timmons opens the song with a soothing introduction, then Jordan steps up first for a deeply compassionate melody and an opening statement exhibiting sensitive delicacy. Timmons comes in next, gently caressing each note of an exceptionally tasteful interpretation. Ware deftly captures the song’s subtle mood on a gorgeously warm solo, followed by Jenkins who concludes the readings and the song with a beautifully tender interpretation.

The first of two tunes from Jenkins’ pen, Princess begins with a collective mid-tempo groove. John starts the opening solo with an articulate tone dispensing absolute joy. Cliff takes the listener for a comfortable joyride on the next statement. Bobby is consistently inventive on the closing performance preceding the quintet’s exit. Side Two starts with Soft Talk by Julian Priester, an energized swinger from the start of the ensemble’s electrically charged theme. Jenkins speaks first to start this scintillating conversation with an aggressive fierceness. Jordan continues the dialogue, making every note count with high voltage power. Jenkins and Jordan soar to great heights in an invigorating exchange over the next few verses. Timmons adds his voice to the discussion next on a heated reading, then Ware walks briskly on an abbreviated statement. Richmond has the last word with energetic drumming in an exciting conversation between both saxes into the reprise and abrupt climax.

Jenkins’ Blue Jay is a laid-back midtempo blues that begins with an unaccompanied lively introduction by Ware, segueing into the quintet’s collective theme. John starts the soloing with an easy-going opening statement. Clifford responds with a marvelous interpretation. Bobby cruises into the third reading with a strong beat and Wilbur steps last into the spotlight for a concise comment that flows effortlessly to the ensemble’s closing chorus and finale. The remastering of Rudy Van Gelder’s original recording has been superbly recreated by Victor Musical Industries with all five instruments full of body, presence, and a vibrant soundstage. If you enjoy good Hard-Bop and are a fan of John Jenkins, Cliff Jordan, and Bobby Timmons, I offer for your consideration, Jenkins, Jordan, and Timmons. An excellent album that in my opinion, no library should be without!

~ Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers (Blue Note BLP 4003/BST 84003), John Jenkins (Blue Note BLP 1573), Them Dirty Blues (Riverside RLP 12-322/RLP 1170) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Tenderly – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2021 by Edward Thomas CarterMore Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Claire Austin was born Augusta Marie on November 21, 1918 to Swedish-American parents in Yakima, Washington. She played in nightclubs throughout the northwest in the 1930s and toured with the Chuck Austin Band in the 1940s.

Retiring from professional singing by the early 1950s, Claire began working as an accountant in Sacramento, California. After singing with Turk Murphy, she frequently performed in San Francisco, California for two years. She remained active through the 1970s.

Vocalist and pianist Claire Austin, whose singing style has been compared to Peggy Lee, passed away on June 19, 1994.

More Posts: bandleader,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano,vocal

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

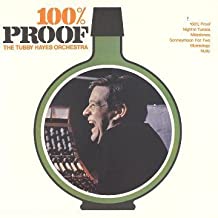

Edward Thomas Harvey was born on November 15, 1925 in Blackpool, England, but grew up in Sidcup, where he attended Chislehurst and Sidcup Grammar School. At the age of 16, he began studying engineering in nearby Crayford and took his first professional job as a musician playing trombone with George Webb and his Dixielanders, a pioneering UK traditional jazz band.

After the World World War II, Harvey joined Freddy Randall and also began performing at Club Eleven in London, England with a number of young musicians, among them Ronnie Scott and John Dankworth who were beginning to experiment with the bebop style that they had picked up from US musicians like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

When the Dankworth Seven formed in 1950, Harvey was a founder member and the percussionist vocalist Frank Holder was also featured in this group. He stayed until 1953, performing on both piano and trombone, and spent the 1950s performing and recording with a number of important UK jazz groups including bands led by Tubby Hayes, Vic Lewis, Don Rendell, and Woody Herman. He also began arranging for groups like Jack Parnell’s Orchestra.

From 1963 to 1972 Eddie was pianist with the Humphrey Lyttelton band. During that time of the early 1970s he also became interested in teaching jazz. His jazz piano course at the City Lit was one of the first jazz education courses in Europe. This led to his writing Teach Yourself Jazz Piano, which was published in the Teach Yourself series. After ten years teaching Music at Haileybury College in Hertfordshire, he accepted the newly created role of Head of Jazz at the London College of Music. Later teaching posts included the Guildhall and Royal Colleges of Music.

Pianist, trombonist, arranger and educator Eddie Harvey, who never led a recording session but was the inspiration for the Richmond Canoe Club Walking Division, passed away on October 9, 2012.

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

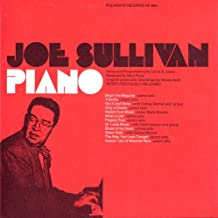

Joe Sullivan was born Michael Joseph O’Sullivan on November 4, 1906 in Chicago, Illinois. The ninth child of Irish immigrant parents, he studied classical piano for 12 years and by age 17, he began to play popular music in silent-movie theaters, on radio stations, and then with the dance orchestras, where he was exposed to jazz. Graduating from the Chicago Conservatory he was an important contributor to the Chicago jazz scene of the 1920s.

Sullivan’s recording career began towards the end of 1927, when he joined McKenzie and Condon’s Chicagoans. Other musicians in his circle included Jimmy McPartland, Frank Teschemacher, Bud Freeman, Jim Lanigan and Gene Krupa. In 1933, he joined Bing Crosby as his accompanist, recording and making many radio broadcasts.

Contracting tuberculosis in 1936, while convalescing at a sanitarium in Monrovia, California in 1937, Crosby organized and appeared in a five-hour benefit for him at the Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, California on May 23, 1937 in front of an audience of six thousand. The show was broadcast over two different radio stations, with fourteen bands attending and raised approximately $3,000 for Sullivan.

After suffering for two years with tuberculosis, Joe briefly re-joined Bing Crosby in 1938 and the Bob Crosby Orchestra in 1939. In 1940, when leading Joe Sullivan’s Cafe Society Orchestra, he had a minor hit with I’ve Got A Crush On You. By the 1950s, he was largely forgotten, playing solo in San Francisco, California, and marital difficulties and excessive drinking caused him to become increasingly unreliable and unable to keep a steady job.

In 1963, he met up with old colleagues Jack and Charlie Teagarden plus Pee Wee Russell when they performed at the Monterey Jazz Festival. Pianist Joe Sullivan passed away on October 13, 1971 in San Francisco at the age of 64.

More Posts: bandleader,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano