Requisites

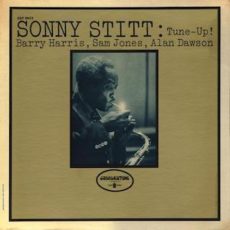

Tune~Up! ~ Sonny Stitt | By Eddie Carter

Sonny Stitt was equally fluent on alto sax (tracks: A2, A4, B2, B3) and tenor sax (tracks: A1, A3, B1, B3) with a pure tone that could be carefree, fiery, or seductive. This morning’s choice from the library is a superb example of him at his best. Tune-Up! (Cobblestone CST 9013) is an excellent 1972 quartet session anchored by Barry Harris on piano, Sam Jones on bass, and Alan Dawson on drums. Stitt’s birth name was Edward Hammond Boatner, Jr. and he came from a musical family. Sonny’s father sang baritone, was a composer, and was a college music professor. His mom taught piano, and his brother was a classically trained pianist. He was later adopted by a family named Stitt and gave himself the name Sonny. The musicians he’s played with reads like the encyclopedia of jazz. Stitt’s also recorded over one hundred albums as a leader and sideman. My copy used in this report is the original US Stereo album.

Side One opens with a speedy rendition of Tune-Up by Miles Davis. Sonny’s tenor sax is emotionally charged from the start of the melody. He launches a ferocious workout on the first statement at breakneck speed. Barry is up next for a vigorously energetic reading leading to a final heated discussion by the leader before the quartet’s exit. I Can’t Get Started by Vernon Duke and Ira Gershwin is a gorgeous song from the film, Ziegfeld Follies of 1936. Stitt’s on alto sax for this tune and shows profound respect to the standard beginning with a thoughtfully tender opening chorus and lyrically beautiful serenade. Harris indulges in nostalgic reminiscing and reflection on the second interpretation and Jones follows with a delicately pretty performance. Stitt makes a genuinely touching and gracefully poignant presentation into the group’s charming climax.

Idaho by Jesse Stone was composed in 1942 and pays homage to the state. This original starts at a jaunty tempo with a cheerful melody. Sonny steps up first with a high-spirited opening statement. Barry takes the reins next for a concise performance of nimble agility. The saxophonist adds a brief bit of fire to the tune with a fitting closer ahead of the quartet’s exit. Side One closes on an upbeat note with a popular song about two lovers who are now Just Friends. It was written in 1931 by John Klenner and Sam M. Lewis. Stitt leads the group through a brisk melody, then kicks it up a notch on the opening chorus with combustible bop chops. Harris fills the second solo with a restless, bristling energy, matched by the rhythm section’s swinging support. Stitt brings out the best on a few final vivacious thoughts preceding the quartet’s closing moments.

Side Two opens on the saxophonist’s slow blues tribute to Lester Young and Charlie Parker, Blues For Prez and Bird. The trio begins with a soulful introduction, then Sonny applies an appropriately warm tone to the melody and first interpretation. Barry is especially endearing on a short statement that swings softly. Stitt arrives at a beautiful conclusion after speaking with deep emotion on the finale. Dizzy Gillespie’s Groovin’ High is a 1945 uptempo standard from the book of Bebop. The quartet comes out cooking on the opening chorus, then Stitt shifts into another gear with a dazzling reading of sheer exuberance. Harris also shows remarkable nimbleness on the second performance matching the saxophonist step for step. Stitt slices through the closing statement with razor-sharpness before the ensemble’s vigorous climax.

I Got Rhythm by George and Ira Gershwin is a jazz standard that was introduced in the musical Girl Crazy (1930). The ensemble deceptively starts slowly at the song’s bridge, rather than the beginning. Sonny has the first solo, erupting on tenor sax with the dynamic force of an active volcano. Barry takes over on the second statement with a fierce intensity, then Stitt kicks up a storm on alto sax for the next presentation. Jones makes a concise comment preceding Stitt ending the song on tenor the way it began. Tune-Up! was produced by Don Schlitten and recorded by Paul Goodman. The album has an exceptionally good soundstage with great clarity throughout the highs, midrange, and bass. If you’re in the mood for an outstanding album of alto and tenor sax, I proudly recommend and submit for your consideration, Tune-Up! by Sonny Stitt. He’s in top form here, and every track’s a winner!

~ I Can’t Get Started, Just Friends, Groovin’ High, I Got Rhythm – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2021 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Eugene Sufana Allen was born on December 5, 1928 in East Chicago, Indiana. He began playing clarinet and piano as a child, and was playing with Louis Prima at age 15 in 1944. He stayed in Prima’s band until 1947, then worked with Claude Thornhill for two years in 1949, and from 1951 to 1953 he played with Tex Beneke.

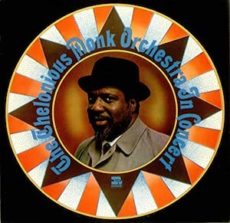

In 1953 he began playing with the Sauter-Finegan Orchestra, playing with them intermittently until 1961, and also worked with Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, and Hal McKusick in the 1950s. Toward the end of the decade, and into the early 1960s, Gene worked with Gerry Mulligan, Manny Albam, Woody Herman, Thelonious Monk, and Bob Brookmeyer.

His later associations include work with Urbie Green, Mundell Lowe, Rod Levitt, and Rusty Dedrick. In the calendar year of 1963, Allen successfully played in and recorded with the big bands of Benny Goodman, Thelonious Monk, and Woody Herman.

Baritone saxophonist and bass clarinetist Gene Allen passed away on February 14, 2008.

More Posts: clarinet,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Paul Desmond was born Paul Emil Breitenfeld on November 25, 1924 in San Francisco, California. His father was a pianist, organist, arranger, and composer who accompanied silent films in movie theaters and produced musical arrangements for printed publication and for live theatrical productions. He started his study of clarinet at the age of twelve and continued while at San Francisco Polytechnic High School. During high school he developed a talent for writing and became co-editor of his high school newspaper.

As a freshman at San Francisco State College he began playing alto saxophone, however, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he spent three years in the Army band stationed in San Francisco. After his discharge in 1946 he legally changed his name to Desmond. Working in the San Francisco Bay Area as a backing musician, occasionally with Dave Brubeck.

Following a breakup and a reunion with Brubeck, the quartet became especially popular with college-age audiences, often performing in college settings like on their ground-breaking 1953 album Jazz at Oberlin at Oberlin College. The group played until 1967, when Brubeck switched his musical focus from performance to composition and broke the unit up. During the 1970s Desmond joined Brubeck for several reunion tours, with Brubeck’s sons Chris, Dan and Darius.

He worked several times during his career with baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, guitarist Jim Hall, Chet Baker, and Ed Bickert. Alto saxophone and composer Paul Desmond, who was one of the most popular musicians to come out of the cool jazz scene, passed on May 30, 1977, not of his heavy alcohol habit but of lung cancer, the result of his longtime heavy smoking.

More Posts: bandleader,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Daily Dose Of Jazz…

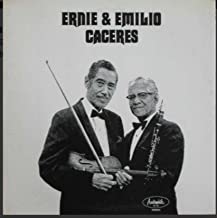

Ernesto Caceres was born on November 22, 1911 in Rockport, Texas and learned to play the clarinet, guitar, alto and baritone saxophone. He first played professionally in 1928 in local Texas ensembles. He and his brother Emilio moved to Detroit, Michigan before moving to New York City, taking work as session musicians. In 1937 they made live nationwide appearances on Benny Goodman’s popular radio series Camel Caravan which created a sensation and made them jazz stars.

In 1938 Ernesto became a member of Bobby Hackett’s band, then worked as a sideman with Jack Teagarden and Glenn Miller’s orchestra from 1940 to 1942. While with Miller, he made an appearance in the films Sun Valley Serenade and Orchestra Wives. Time with Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, and Tommy Dorsey followed later in the 1940s. In 1949 he put together his own quartet, playing at the Hickory Log in New York. He was a frequent performer with the Garry Moore Orchestra on television.

At the beginning of the 1960s he played with the Billy Butterfield Band. In 1964 he moved back to Texas and played in a band with brother Emilio from 1968 until his death. He spent some time in 1965 and 1966 at Mint Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada and at the Holiday Hotel in Reno, Nevada with the Johnny Long Band. Saxophonist, clarinetist and guitarist Ernesto Caceres passed away from cancer on January 10, 1971.

More Posts: bandleader,clarinet,guitar,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

Requisites

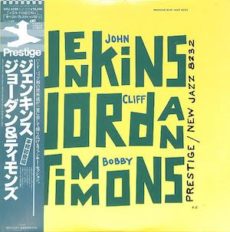

John Jenkins, Cliff Jordan, Bobby Timmons | By Eddie Carter

I begin this morning’s discussion with the 1960 collaborative album, Jenkins, Jordan, and Timmons (New Jazz NJLP 8232) by John Jenkins, Clifford Jordan, and Bobby Timmons. Joining them on this date are Wilbur Ware on bass and Dannie Richmond on drums. My copy used in this report is the 1981 Japanese Mono reissue by Victor Musical Industries (New Jazz SMJ-6299). John Jenkins’ approach to Hard-Bop and standards on the alto sax was distinctively tasteful. His solos always showed respect and affection for the tunes he played, and he could bring imaginatively unique lines even to well-worn standards. His other album as a leader is the self-titled release, John Jenkins (1957). Clifford Jordan’s interpretations on the tenor sax were the perfect characterization of his sound, sometimes growling, sometimes purring, but always with a formidable technique and a passionately assertive tone. Here, Jordan is in great form with another horn to joust with.

Pianist Bobby Timmons was one of the most talented yet neglected figures in the annals of Jazz. He composed two songs that are etched in the minds of many Jazz fans, Dat Dere, a mainstay in the early days of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet and Moanin’ that became a huge hit for The Jazz Messengers. Timmons appeared on the landmark album, Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers (1958). On this date, he approaches each tune with a melodic and rhapsodic touch that’s irresistible. Wilbur Ware was an extraordinary soloist on the bowed bass; he possessed a beautiful sound that could be fat, resonant, and fluid without any loss of body on any of the songs he played. Dannie Richmond is best known for his many albums with Charles Mingus, he’s a very pleasant surprise on this record with an energetic liveliness in his playing. He also recorded with many jazz greats including George Adams, Pepper Adams, Chet Baker, Ted Curson, Booker Ervin, Duke Jordan, Herbie Nichols, Horace Parlan, and Don Pullen.

Clifford Jordan’s Cliff’s Edge starts Side One at midtempo with both saxes flexing their muscles in unison on the opening chorus. Cliff is up first with a very satisfying opening solo at an easy, unhurried pace. John continues the conversation with a pleasant zest on the second performance. Bobby tells his story last with a charming interpretation that comes across effectively anchored by Wilbur and Dannie’s support into the quintet’s ending. Up next is the 1946 jazz standard Tenderly by Walter Gross and Jack Lawrence. Timmons opens the song with a soothing introduction, then Jordan steps up first for a deeply compassionate melody and an opening statement exhibiting sensitive delicacy. Timmons comes in next, gently caressing each note of an exceptionally tasteful interpretation. Ware deftly captures the song’s subtle mood on a gorgeously warm solo, followed by Jenkins who concludes the readings and the song with a beautifully tender interpretation.

The first of two tunes from Jenkins’ pen, Princess begins with a collective mid-tempo groove. John starts the opening solo with an articulate tone dispensing absolute joy. Cliff takes the listener for a comfortable joyride on the next statement. Bobby is consistently inventive on the closing performance preceding the quintet’s exit. Side Two starts with Soft Talk by Julian Priester, an energized swinger from the start of the ensemble’s electrically charged theme. Jenkins speaks first to start this scintillating conversation with an aggressive fierceness. Jordan continues the dialogue, making every note count with high voltage power. Jenkins and Jordan soar to great heights in an invigorating exchange over the next few verses. Timmons adds his voice to the discussion next on a heated reading, then Ware walks briskly on an abbreviated statement. Richmond has the last word with energetic drumming in an exciting conversation between both saxes into the reprise and abrupt climax.

Jenkins’ Blue Jay is a laid-back midtempo blues that begins with an unaccompanied lively introduction by Ware, segueing into the quintet’s collective theme. John starts the soloing with an easy-going opening statement. Clifford responds with a marvelous interpretation. Bobby cruises into the third reading with a strong beat and Wilbur steps last into the spotlight for a concise comment that flows effortlessly to the ensemble’s closing chorus and finale. The remastering of Rudy Van Gelder’s original recording has been superbly recreated by Victor Musical Industries with all five instruments full of body, presence, and a vibrant soundstage. If you enjoy good Hard-Bop and are a fan of John Jenkins, Cliff Jordan, and Bobby Timmons, I offer for your consideration, Jenkins, Jordan, and Timmons. An excellent album that in my opinion, no library should be without!

~ Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers (Blue Note BLP 4003/BST 84003), John Jenkins (Blue Note BLP 1573), Them Dirty Blues (Riverside RLP 12-322/RLP 1170) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Tenderly – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2021 by Edward Thomas CarterMore Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,piano,saxophone