Daily Dose Of Jazz…

Claire Daly was born on February 26, 1959. At the age of 12 she began playing the saxophone and was soon turned onto jazz by way of a live performance by the Buddy Rich Big Band. She went on to attend Berklee College Of Music and upon graduation she became a full-time professional musician.

In the late 70s and early 80s Claire played with various groups in the jazz and rock arenas, and her powerful tenor saxophone suited the latter perfectly. However, playing more jazz than rock, Daly switched to the baritone saxophone and has worked in New York City since the mid-80s.

>A seven-year association with the all-female big band, Diva, was followed with her working with People Like Us. Daly’s versatility moves between jazz, R&B and Latin, releasing two CDs as a leader for Koch Records and three on her own label DalyBread.

Her influences include Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Sonny Rollins and, on baritone, Serge Chaloff, Ronnie Cuber and Leo Parker. She has performed with Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Joe Williams, and Rosemary Clooney among many others, and her first CD Swing Low resides in the William Jefferson Clinton Library in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Claire Daly, a gifted improviser whose rich tone and emotional depth has earned her a place as a respected member of the baritone saxophone family, continues to lead her own jazz groups and to pass the gift of music on to the next generation.

Diagnosed with head and neck cancer in 2023, baritone saxophonist and composer Claire Daly died at the residence of a friend in Longmont, Colorado, on October 22, 2024, at the age of 66.

More Posts: saxophone

Requisites

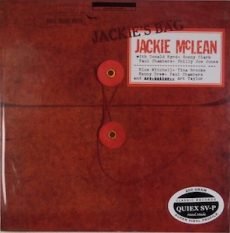

Jackie’s Bag ~ Jackie McLean | By Eddie Carter

Alto saxophonist, Jackie McLean, enters this morning’s spotlight with an excellent 1961 hard bop album, Jackie’s Bag (Blue Note BLP 4051/BST 84051). It comprises two sessions from 1959 and 1960, and two all-star ensembles join him. Donald Byrd (tracks: A1-A3), Blue Mitchell (B1 to B3) on trumpet, Tina Brooks (B1 to B3) on tenor sax, Sonny Clark (A1 to A3), Kenny Drew (B1 to B3) on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, Philly Joe Jones (A1 to A3), and Art Taylor (B1 to B3) on drums. The copy I own is the 2008 Classic Records mono audiophile deep groove reissue, sharing the original catalog number.

Side One opens with Quadrangle, the first of five originals by Jackie McLean. It takes off straight into the stratosphere from the start of the quintet’s brisk melody. Jackie takes a sharp corner into an energetic opening solo, then Donald continues navigating traffic in the next lively statement. Philly Joe tackles the final solo vigorously, leading back into the closing chorus. Blues Inn begins with the ensemble’s relaxed theme. McLean opens with an easygoing solo, then Byrd compels the listener to leave their troubles behind in the following statement. Clark has an enjoyable interpretation next, and Paul’s short walk leads the group back into the theme’s restatement and close.

Fidel gets going with Philly Joe’s introduction to the group’s upbeat melody. Donald has the first solo and makes the most of every note. Jackie takes over and swings so passionately that the listener is sure to be tapping his toes and snapping his fingers. Sonny’s rhythmic agility in the closer flows efficiently into the closing chorus and ending. Appointment in Ghana starts the second side with the front line’s introduction segueing into the sextet’s lively melody. McLean leads off and shows he can cook with the best of them. Mitchell adds some bite to the second solo, then Brooks ignites the next reading with plenty of heat. Drew gets the last word ahead of the group’s tasty finale.

A Ballad For Doll is a heartfelt tribute from Jackie to his wife, Dolly. The sextet gently slows things down for a warm and affectionate opening chorus. Kenny shines in the solo spotlight with a delicately beautiful interpretation that builds into the group’s touching climax. Isle of Java by Tina Brooks brings the album to a close, picking up the tempo one last time for Brooks, setting the spirited melody in motion against the sextet. McLean comes out swinging first with a lively interpretation. Mitchell maintains the groove with an effervescent solo. Brooks responds with a statement full of zest. Drew is on the trail of the front line in the following reading, and Chambers gets a moment to shine, preceding the theme’s reprise and fadeout.

Alfred Lion produced Jackie’s Bag, and Rudy Van Gelder managed the recording console. The album’s sound quality is clean and crisp, leaping from the speakers with stunning fidelity and absolutely no background noise. Bernie Grundman mastered the audiophile reissue, and the record was pressed on 200-gram Quiex SV-P Hand Made Super Vinyl. The record is also silent until the music starts. If you’re in the mood for an excellent hard bop album, Jackie’s Bag, by Jackie McLean, is an outstanding entry point to his artistry and discography. The album also offers a vivid picture of the music landscape in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and should make a welcome addition to any jazz fan’s library!

© 2026 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone

LANGSTON HUGHES & HIS QUARTET

Experience an unforgettable evening of modern jazz with saxophonist Langston Hughes IIand his Quartet. Rooted in gospel and shaped by the rich traditions of jazz, Langston’s music is a soulful, high-energy journey through sound, storytelling, and spirit. With a style that is both deeply expressive and rhythmically driven, the quartet delivers performances filled with passion, beauty, and joy.

Hughes is an accomplished saxophonist, woodwind doubler, composer, and educator, rapidly emerging as one of the most exciting young voices in jazz today. Originally from the Washington, D.C. area, Langston began his musical journey in the Prince George’s County public school system before studying at Howard University under the mentorship of Charlie Young III and Cyrus Chestnut. He recently earned his Master’s degree in Jazz Studies from The Juilliard School. Langston has toured with Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, performs with Cyrus Chestnut, Rufus Reid, and is a member of Ulysses Owens Jr.’s Generation Y Band.

Langston is also an in-demand woodwind performer on and off Broadway, with recent credits including A Wonderful World: The Louis Armstrong Musical and Just in Time: The Bobby Darin Story. A former Strathmore Artist in Residence and a graduate of the Kennedy Center’s Betty Carter’s Jazz Ahead, he is also a dedicated educator, teaching privately and through FAME, committed to uplifting the next generation of artists.

Langston Hughes II ~ saxophone

Robert Papachica ~ guitar

William Hill III ~ piano

Eytan Schillinger-Hyman ~ bass

Quincy Phillips ~ drums

Tickets: $35.00 ~ $40.00 +fee

Streaming: $15.00 +fee

More Posts: bandleader,club,genius,instrumental,jazz,music,preserving,saxophone,travel

BRAXTON COOK

Maryland’s own Braxton Cook is an Emmy Award-winning, two time Grammy Award winning, NAACP Image Award-nominated artist, known for his world-class skills as an alto saxophonist, vocalist, songwriter, producer and composer. With a blend of jazz, soul, and alt-R&B, he has carved out a unique, melodic sound that has made him one of the most exciting voices of his generation. A Juilliard-trained, genre-jumping artist whose music feels both contemporary and timeless, Braxton studied saxophone under the renowned Paul Carr. During this time, Braxton was selected as a semi-finalist in the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Saxophone Competition.

He has performed on major stages around the world, from Coachella to international jazz festivals, and collaborated with artists like Rihanna, Solange, Christian McBride Big Band, Tom Misch, Christian Scott, Marquis Hill, and Jon Batiste, performing on his soundtrack for Pixar’s Oscar-winning film, Soul. His albums garner critical acclaim from outlets like Billboard, BET, NPR Music, FORBES, and The Washington Post, cementing Braxton as both a “jazz marvel” and a cultural influencer shaping modern music. His newest album, Not Everyone Can Go, drops August 29th. Musically, the album conjures images of bright evening sunshine, when the temperature begins to cool.

Braxton Cook ~ saxophone & vocals

Mike King ~ keyboards

Paul Reinhold~ bass

Curtis Nowosad ~ drums

Tickets: $35.00 ~ $40.00 +fee

Streaming: $15.00 +fee

More Posts: bandleader,club,genius,instrumental,jazz,music,preserving,saxophone,travel,vocal

Requisites

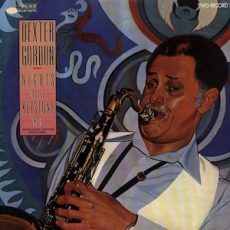

Nights At The Keystone ~ Dexter Gordon | By Eddie Carter

Dexter Gordon’s return to the United States generated significant excitement among his fans. After his triumphant return to the Village Vanguard and his 1976 performance, which produced the album Homecoming, he began touring regularly. This morning’s album from the library features the tenor saxophonist and his quartet at one of San Francisco’s notable jazz clubs. Nights At The Keystone (Blue Note BABB-85112) is a two-record set documenting his performances over several nights in 1978 and 1979 at the Keystone Korner. George Cables on piano, Rufus Reid on bass, and Eddie Gladden on drums round out the group. The copy I own is the 1985 U.S. stereo release.

The album opens with the quartet’s tender rendition of Sophisticated Lady by Duke Ellington. Dexter introduces the song with a dreamy melody, which he sustains with remarkable sensitivity in his opening statement. George’s subsequent solo evokes a bygone era of innocence and joy. Dexter returns to add a few final gentle thoughts before the closing ensemble and audience’s applause. Gordon speaks to the audience and introduces It’s You or No One by Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn. The quartet launches into a spirited theme, then Gordon takes charge on the first solo, soaring into the stratosphere. Cables tackles the following solo at a brisk pace, then Gordon trades lively choruses with Gladden, paving the way for a swift return to the theme and a spirited finish.

The rhythm section opens Dexter Gordon’s Antabus with an energetic introduction. The quartet then is off to the races with a brisk melody. Dexter ignites the opening interpretation with fiery tenor saxophone lines. George continues cooking with agility in the following statement, then Dex takes the reins again briefly before the quartet takes the song out. Easy Living by Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin comes from the 1937 film of the same name and slows the ensemble down for the pianist’s introduction, segueing to the quartet’s gentle theme. Dexter’s opening statement is sure to melt all the tension in your body away with delicacy and tender warmth. Cables responds with a deceptively elegant approach that picks up the pace to midtempo ahead of Gordon’s return for the theme’ restatement and ending.

The tempo moves upward again to begin side three with the quartet’s lively version of Tangerine by Johnny Mercer and Victor Schertzinger. The rhythm section provides a lush foundation for Dexter’s melody to flow comfortably at an easy beat. Dexter takes the spotlight first with a down-home, soulful flavor that swings from the first note to the finale. George has the next spot and makes his presence felt preceding the closing chorus. More Than You Know by Vincent Youmans, Edward Eliscu, and Billy Rose begins with the group’s elegantly graceful introduction and melody. Gordon again shows off his sentimental side with a hauntingly tender lead solo. Cables steps up next for a short, serene statement that builds as it unfolds. Gordon has the final say ahead of the group’s gorgeous finale.

Side Four concludes the album with Come Rain or Come Shine, by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, giving everyone a lengthy solo. The quartet’s medium tempo sets the song’s introduction and opening chorus in motion. Dexter is up first with a neatly paced stroll, then George delivers a splendid performance. Rufus walks with a soulful groove next, and Dexter and Eddie engage in a brief exchange before the quartet’s return and finale. Todd Barkan produced Nights at the Keystone, and Rich McKean managed the recording console. Malcolm Addey was the mixing engineer, and Rudy Van Gelder mastered the album.

The sound quality of this live album is exceptional, truly capturing the ambiance of Keystone Korner and offering an impressive soundstage that highlights The Dexter Gordon Quartet at their finest. If you’re searching for a top-notch live performance by one of jazz’s legendary tenor saxophonists, Nights at the Keystone by Dexter Gordon is well worth checking out during your next visit to the record store. It spotlights the tenor saxophonist in peak form, blending technical brilliance, improvisational flair, and deep musical chemistry throughout the set!

~ Homecoming (Columbia PG 34650) – Source: Discogs.com ~ Come Rain or Come Shine, Easy Living, More Than You Know, Tangerine – Source: JazzStandards.com © 2026 by Edward Thomas Carter

More Posts: choice,classic,collectible,collector,history,instrumental,jazz,music,saxophone